Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

I am at the famed Ukrainian Veselka diner on 2nd Ave. and 9th waiting on the legendary writer, musician, and Afro-Bohemian Godfather Greg Tate, who just texted that he is in Brooklyn dropping off his grandson and needs another 30 minutes. This delay is good because now I have time to make a few calls and sign copies of my hot off the press double vinyl album. I am hyped to show Greg how his liner notes came out and thanked him again for his contribution. His gift of riveting language paired with a superpowered intellect is a sight to see, especially when it comes to music. Also, I hadn’t been able to rap with the legend face to face in a minute, the last time being when I picked him up at the airport in Sarasota to take him to his awaiting father after the passing of his mother, Florence, who was one of my dear buddies and art commensurators.

I love being in New York City in all of its pseudo-post-COVID self, even with all the makeshift sidewalk and curbside eating cabins, and vax-card border stops. The weather is unusually warm for November, but the rhythm of movement is familiar. The rising buildings, fast-moving people, and speedy ebikes all indicate a sense of recovery and human resilience that is remarkably New York, a place of art, ideas, and connections. And when I am here, I always take in the sights like a tourist, scout opportunities like a Wall Street analyst, and visit friends like a relative.

Greg Tate is always on my check-in list. I appreciate his multi-portal approach to analysis and creative processing and the way he flowed from writing to music to producing conceptual quiltmaking that connects ideas, places, and people through stimulating and revelatory schematics for the advancement of colored people. His writing has that bop hop flow, academic know, and hip-hop show, all roped together in a way that might strangle you, lifeline you, or both. His work at the Village Voice was foundational in bringing a voice, advocacy and constructive criticism to Black culture. And he was on the front lines of championing hip-hop as a serious thing. He was a founding member of the Black Rock Coalition and along with In Living Color’s Vernon Reid. His book Flyboy in the Buttermilk: Essays of Contemporary America pioneered a new Black Aesthetic, and still serves as a blueprint of how to engage the complexity, nuance, and magic of Black life. And as a musician and bandleader of Burnt Sugar he was always pushing sonic spaces.

I have been so fortunate to have Greg contribute to several different projects of mine. He and his Burnt Sugar band performed a funkified version of “Dixie” for me at the Bowery Poetry Club way back in 2008. I invited him to do a panel at the Dorsky Gallery in Queens for a show featuring my Pi quilts, and he came down to play my first performative “SquareRoot of Love” dinner in Sarasota. Later, he also did the liner notes for my music project, AfroDixieRemixes. His range of engagement, genius curiosity, and capacity to connect is why he is the “Mayor of Black Bohemia at Cultural Provocateur.” This brother has been so supportive in words and in action not only to me but countless others, which is why I have to check in with him.

Greg texts me again that he needs another 20 minutes. I text back with “no worries.”

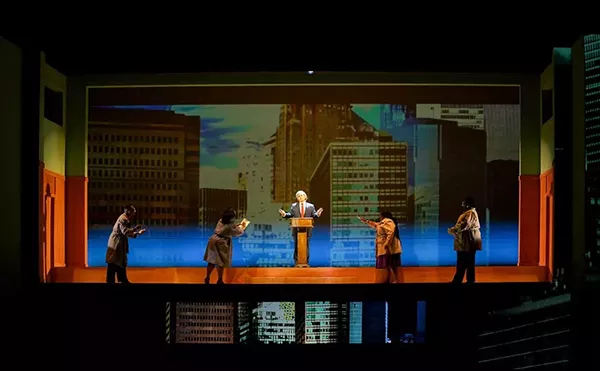

I am in New York doing a month-long residency at La Mama Experimental Theater Club, developing a series of performances, which explores and responds to the major fault lines of 2020: the pandemic, American policing, and Confederate monuments and iconography. I am still trying to figure it all out. I still need an actor and a dancer. I am sure Greg has some recommendations with his incredible network of Black creatives.

I look up and there is Greg with his signature scarf, hat, and shoulder bag. We quickly get into it like old times. He orders a veggie burger and I get an omelet. I ask about Natasha, Mike Veal, Bahiyyah, and his brother Brian. I get the 411 on the ever-changing complexion of Harlem. I tell him my homie Suesan Stovall says hello, he perks up and tells me that she was a founding member of the Black Rock Coalition.

Before the next round of coffee, I hand him the albums, showing him the text layout of his essay. He digs it. We talk about the comeback of vinyl. In a matter of two hours we talk about AfroFuturism, the Dirty South exhibition, the pandemic, George Floyd, Alpo Martinez, Prince and his untimely death, the publishing industry, the brilliant writing of Steven Thrasher, and how he thinks veggie burgers are done better in Harlem. We rap about Jake-Ann Jones’ new book, Sometimes Farmgirls Become Revolutionaries, written with and about Florence Tate, for which he wrote the foreword. Greg is especially proud of how the book came out and thinks Jake-Ann did a great job. I tease him about seeing him in every music documentary.

We also talk about the future. I ask him if he plans to retire in New York or go to Florida like his parents did, which was certainly a joke on my part because I know he ain’t leaving Harlem. He talks about his plans to self-publish a collection of essays and do some music gigs on the west coast in the spring. I tell him I will probably do a residency at the Exploratorium science museum in San Francisco for Pi Day in March, and how my next music project will be something on Pi and I want him in on it. We talk about meeting up in the Bay Area and doing something dope connecting mathematics and music.

It is time to go, so I remind him about my opening at La Mama coming up soon, and how I want him to see the world’s largest AfroConfederate Battle flag which was a part of the show. He is game and mentions he might want to use it for a Juneteenth event he is working on, and that he would send me the names of potential folks for my performance. We hug goodbye and take some selfies.

Two weeks later, I am back at Veselka, at the same table in the same chair, looking over an empty table with a copy of The New York Times that contains Greg’s obituary. I hadn’t seen him since our breakfast. He had texted me hours before my opening to say that he was not feeling well lately, and would not make it, but wanted to wish me good luck. A few days later he would be gone. There is a permanent loss here. I am in a numb state of shock and disbelief. The planet surely slowed its rotation for the heavenly departure of a giant.

Rest in Peace, Power, and righteous Provocation Brother Greg, in knowing that your work and energy have shaped key elements of American culture and will continue to vociferously vibrate along the main avenues and arteries of Black life. I thank you deeply for being a brilliant thinker, champion, soul brother, mentor, coach, cheerleader, comrade, connector, articulator, and visionary for the culture, for our people, and for me. Thank you, Greg Tate.

John Sims, a Detroit native, is a multimedia creator, writer, and activist, creating projects spanning the areas of installation, text, music, film, performance, and large-scale activism. His main projects are informed by mathematics, the politics of sacred symbols/anniversaries, and the agency of poetic text.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Reddit.