With the Kennedyesque mayor Jerome P. Cavanagh at the helm, there was a whole lot of buffing going on as Cavanagh, with the help of the positivity exuded by the man behind AMC’s the rambler, George Romney, Detroit was being billed as a kind of Model City. The jewel in the crown of Detroit was to have been the 1968 Olympics. The reader will have to read Marraniss’ see how this promising drive led to heartbreaking and seemingly unjustified failure.

Using the novelistic sweep of a doorstopper novel in less than 400 pages, Maraniss has no fewer than a dozen major characters and a host of clearly-delineated minor ones to piece together a narrative that shines with brightness and yet concludes with a kind of sword of Damocles dangling overhead at its end. Like a good novelist, Maraniss does not comment on the “performances” of his “characters.” He could have made a case that the Rev. Albert Cleage was a “negative” segregationist in the face of Martin Luther King’s march with city leaders down Woodward on his way to Cobo Hall where King’s nascent “I Have a Dream” speech was delivered. But Maraniss, like the best novelists, does not notably tip his hand to “play favorites.”

If, however, there is a “hero” of the book, Maraniss seems willing to push Walter Reuther to the fore. Amid violence, Reuther not only showed guts and determination as the leader of the United Auto Workers and all that it entailed regarding civil rights for blacks, but also his constant lobbying with Presidents Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson:

Johnson called Reuther’s hotel room in Washington [Reuther had an almost permanent room, convenient for Presidential meetings] one day after Kennedy’s assassination to say that he needed the labor leader’s help more than ever.

Reuther yearned to be near the center of power and Johnson was masterly of the twin arts of flattery and manipulation. … As frequently as Reuther’s contact had been with the White House during the Kennedy years [Reuther met with Kennedy privately or in small groups 22 times during JFK’s truncated rein as President.], his interactions with Johnson were more intimate.

David Maraniss has always written like a novelist. This not-so-old newspaperman understands that the worst sin a writer can make is to go unread. Like good fiction, David Maraniss’ non-fiction keeps rolling and his concluding paragraphs of each chapter at once conclude a unit and foretell that which is to happen. Maraniss concludes his first chapter with a wrapping up of the extraordinary coincidence of the trashing of the largest black hotel in the land, the Gotham, and the burning of the Ford Rotunda on the same day:

The hotel that Langston Hughes had declared a miracle, that fed Joe Louis his eggs and steak, that displayed Martin Luther King’s civil rights book in every room was giving way to change, for better and worse. Some part of Detroit was dying at the Gotham with every swing of the ax and blow from a sledgehammer, as surely as it was dying twelve miles away, where young Bob Ankony watched an an inferno render the Ford Rotunda into smoldering ruins on that same November day.

Unlike the academic writers of Michigan history — Thomas Sugrue, Nelson Lichtenstein, and Sidney Fine — Maraniss writes with the thrust of readability. I am of the generation that read the works of the academics above, but it was rough going. I felt like I was doing homework.

I don’t know exactly when non-academic writings splashed into the literary world, but when Robert Caro published his mammoth The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York in 1974, it was a kind of announcement that the likes of Richard Sewell’s two-volume biography of Emily Dickinson, a kind of fortress of academic scholarship (Emily didn’t get born until volume two) was on the way out. Who was this biography written for? Clearly, other academics.

It’s true: Caro’s biography of Moses was too long. It took me almost a year of on-and-off reading to finish. But I never thought of putting it aside because the story was so good — those exploratory rowboat trips Moses took envisioning what became Jones Beach, his invention; the way he treated his secretaries, that they could not leave work for the day until his desk was free of paperwork; and his poor brother, a highly-competent architect so badly squeezed by Robert that he couldn’t work in Manhattan and was able to only rent a flat six stories up with no elevator access. I mention these scenes because this is how the reader can “see” what is written about.

Maraniss is not lavish in his descriptions of the dozen or more important characters in his narrative, but he is at once descriptive enough so the reader can see and get a good sense of that character. Thus, the reader understands that UAW leader Walter Reuther is as important as anyone else in his teeming narrative:

With his red hair and boyish mug, Reuther was a confident, straight-ahead personality with a philosophical beat and a complicated take on the political swirl around him. … From his earliest years, his German immigrant parents, Valentine and Anna, veterans of West Virginia’s coal wars, bathed Walter and his siblings in the idealistic waters of socialism.

Another of those major figures, the then recently-elected Governor George Romney, is followed immediately after a half-page on Reuther with an astute summation of the Reuther-Romney relationship. Romney had provocatively called Reuther “the most dangerous man in Detroit” because of his ability to bring about “the revolution without seeming to disturb the existing norms of society.” Maraniss admits that this was “an odd declaration, as much grudging praise as damning criticism, [that] they found themselves at times working in concert, agreeing to the industry’s first profit-sharing plan for workers.”

It is this kind of evaluative writing that distinguishes itself from the three historians mentioned above, particularly Fine’s Violence in the Model City: the Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations and the Detroit Riot of 1967, an overstuffed compendium of undigested information wherein each of the 43 deaths are accounted for, Wikepedia-style.

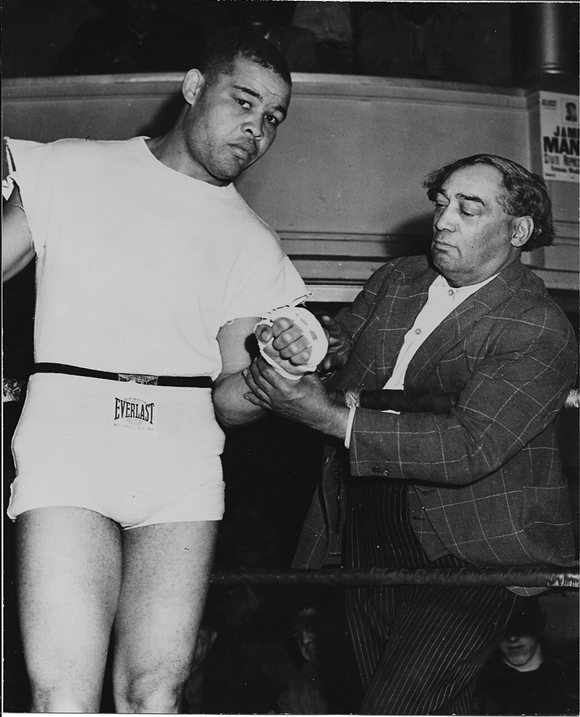

Illustration from 'Once in a Great City'

Joe Louis, left, and the intriguing Henry Johnson, right. Referred to in Maraniss' account as "Pappa Dee," a driver, Johnson was a hustler in the black community who ran a barbershop and "managed" boxers.

Maraniss wouldn’t dare to go down Fine’s path in telling his chunk of the Motown story. After his chapter on the signal events of the trashing of the Gotham Hotel and the burning of the Ford Rotunda, Maraniss shows that the demise of the Gotham, where the crème of black social life converged and is seen as one of the steps of the ongoing “Negro removal”; this phenomena, dictated that blacks be shunted aside for “progress” of the city. The police raid of the Gotham was ostensibly engineered to rid its premises of a numbers operation, which Maraniss does not deny, but by implication Maraniss gives a colorful rendering of positive, social black life with an almost Whitmanesque rendering of clientele, again beginning with Joe Louis, who

became a breakfast regular in the Gotham’s Ebony Room, ordering five scrambled eggs with ketchup and a bone-in steak. … Sammy Davis, Jr., rented the entire fifth and sixth floors during stays in Detroit. B.B. King got married in Room 609. Louis Armstrong’s valet would wash fifty handkerchiefs a night in the hotel laundry.

There is also an auspicious appearance by Martin Luther King, Jr., who turns out to be one of the main characters in Maraniss’ narrative. When King visited the Gotham in 1959, he inspired owner John White to leave a copy of one of King’s civil rights books in every room to go along with the Bible. As a major character, one responsible for the book’s most significant event, King’s March to Freedom with other Detroit leaders down Woodward Avenue and the ensuing rally in Cobo Hall, Maraniss’ account is inlaid with the skill of an adroit novelist. Thus, while the reader may initially surmise that Maraniss is something of a name-dropper, this isn’t the case; one can be sure that he will pick up the thread of each important character as the narration proceeds. Each of the important characters who participates in the march is shown with his reactions in the manner of a character in a novel of convergence. It is in this way that the Rev. C. L. Franklin is depicted (he doesn’t actually get into the rally in Cobo Hall) as Maraniss depicts his conflicting allegiances, particularly those with the Rev. Albert Cleage, who was decidedly against the march and didn’t participate.

While I have been a Detroiter since 1978, I made little effort to steep myself in the lore of the city until the early 1990s. Despite an immersion of more than two decades, I was surprised to find that Maraniss was able to reveal many details about Detroit that I was unaware of. Here are two: 1) That when the Book Cadillac Hotel opened in the 1920s, it was the largest hotel in the U.S.; 2) Not only did the advertising firm of J. Walter Thompson have offices in the Buhl Building in Detroit, but its No. 1 client was Ford Motor Company. Again, these two chunks of information are hardly extraneous to Maraniss’ story. The Book housed Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, both important characters in the Detroit story. The stories of Henry Ford and Henry the Deuce (HD2) and Lee Iaacoca are also woven into Maraniss’ literary fabric.

If the story of Walter Reuther features more significantly than that of any other character in Maraniss’ sweep, it is the capper of LBJ that finishes off the “story” with the most import. If JFK had (to use the phrase that he has been labeled with) to be dragged kicking and screaming into the Civil Rights era, LBJ was ready to persevere for Civil Rights equality before Kennedy was buried and was ready to launch his Great Society program with his announcement of his plans in Ann Arbor just six months to the day into his Presidency.

There are heartbreaking stories leading to the disappointment of the International Olympic Committee rejecting Detroit to host the ‘68 Olympics. Prominent among these is the tale of the open-housing question—that Detroit did not allow blacks to be housed in many areas of the city. Only two counsel members, one white, Mel Ravitz, and one black, William T. Patrick, Jr., both of whom “stood together on the Lincoln memorial steps after the [March on Washington], hand in hand, and sang freedom songs, then returned to Detroit with an ever deeper commitment to push open-housing legislation they had co-sponsored that summer.”

A full-scale biography has yet to be written on Mayor Jerome P. Cavanagh, one that must turn on the irony that he was at the helm in 1967, when the Riot changed Detroit forever and yet he was the most forward thinking of Detroit mayors in terms of Civil Rights. Before the council vote on open housing was conducted, Cavanagh issued a statement two weeks before:

I would have remained silent. … To do so would have been politically expedient. I cannot in good conscience choose this course [to endorse closed housing for blacks]. I believe that discrimination is evil. It runs counter to everything that I have been taught about any religious obligations and my obligations to my fellow citizens. … The Detroit approach substitutes words for bricks, peace for violence, tolerance for bigotry, and understanding for hate.

On Oct. 8, Detroit City Counsel voted 7-2 to defeat the bill for open housing, with only Ravitz and Patrick in favor. In response to the defeated bill, civil rights activists spread leaflets meant to be heard on the other side of the globe where the fate of Detroit’s candidacy was being decided: “America does not deserve the 1968 Olympics. Fair play has not become a living part of Detroit and America for all citizens.”

The Detroit era covered by Maraniss is best known for Motown, and there have been many volumes covering its phenomena and the source from which it sprang, Berry Gordy. That Gordy’s genius for creating Motown was both an artistic and monetary success is undeniable; the early echoes of the Civil Rights movement as engineered by Gordy with the Motown Review and the foresight to record MLK’s speeches clearly demonstrate he was something of a Renaissance Man who more than anyone else put Detroit U.S. map in a city known for little more than cars.

Though it is beyond the scope of the 18 months Maraniss has carved out for his portrait, he makes scant reference to Gordy’s 1972 move to Los Angeles and his ostentatious moves into moviemaking. And Moraniss makes no forays into the bitterness felt by many who feel they weren’t given a fair share of the pie. But Maraniss concludes on an eloquent note, not so much for the cute working in of Motown lines, but as for its final sentence:

And here came the heat wave and the quicksand and we all had nowhere to run and nowhere to hide and we came and got those memories. What lasts? What did Detroit give America?

You could hear the answer in every song.

It should not be a surprise to the reader that, even though he concludes his introduction with “Even then [the 18 months covered in this book], some part of Detroit was dying, and that was where the story begins.” Two sentences before, Maraniss deftly plants the irony that “life can be luminous when it is most vulnerable.”