Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

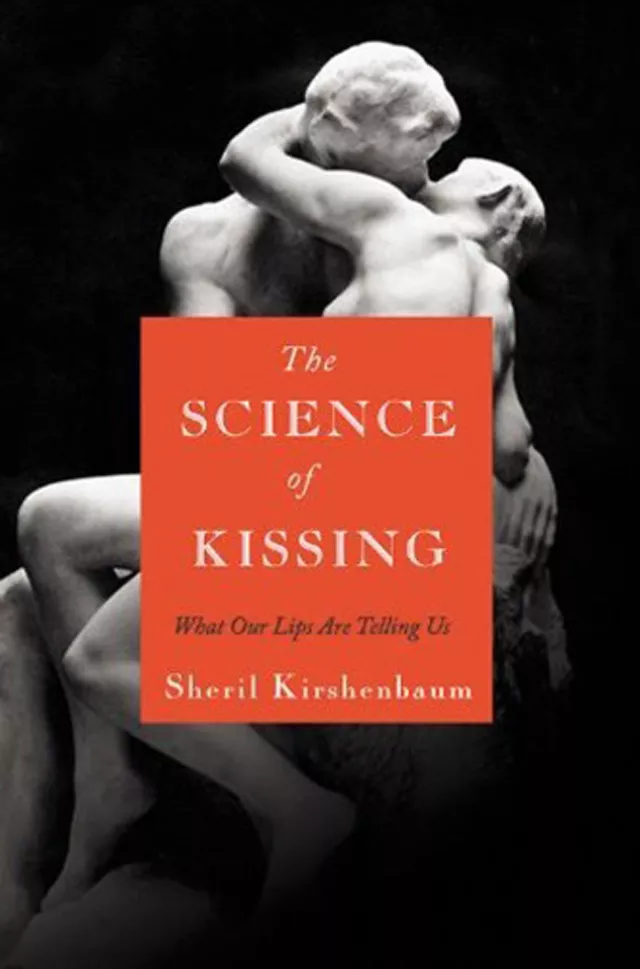

The Science of Kissing: What Our Lips Are Telling Us

by Sheril Kirshenbaum

Grand Central Publishing, $19.99, 272 pp.

The year is still young, but Sheril Kirshenbaum has already written a standout among nonfiction titles of 2011. As a science writer, Kirshenbaum has penned thoughtful and engaging articles about science literacy, environmental science and education for the likes of Salon, The Huffington Post and Mother Jones. As a research associate at the University of Texas' Center for International Energy and Environmental Policy, she works to enhance public understanding of energy issues. She is an adviser to NPR's Science Friday and co-hosts the Discover magazine blog The Intersection. But for all her accomplishments and accolades, her latest project borders on the super-genius. For the past two years she has been investigating the biology, anthropology, psychology and cultural history of osculation. It's called embrasser in French, besar in Spanish; any online translator can offer you the appropriate character translations in Arabic, Korean, Japanese and Pashto. You've probably known it since childhood simply as kissing.

Kirshenbaum approaches science writing not as the highly educated expert talking down to a layperson — though she holds two master's of science degrees — but rather as a learned peer having a casual conversation. Think of talking to your friend's cooler, older sister about all those bands and records she heard that you didn't. Only in this case, Kirshenbaum is schooling you on the intimacy of bonobos, that most amorous great ape.

Lighthearted is the appropriate tone. As Kirshenbaum recounts in her introduction, kissing is a subject that everybody feels they know at least something about. Specific scientific disciplines have produced their own takes on the practice, but science at large hasn't tried to aggregate that knowledge into an overarching theory on this common, worldwide, and in some cases trans-species practice. She writes, "Microbiologists will tell you that it is a means for two people to swap mucus, bacteria and who knows what else," but also wonders, "Why would this mode of transferring germs evolve? And why is it so enjoyable when the chemistry is right?"

It's a simple approach that only occasionally borders on the simplistic. Kissing is organized into three sections: The first is a brisk tour of kissing's biological and cultural history; the second looks at the body's physiological responses during kissing. The book is less than 300 pages, which means both of these vast subject areas are covered quite quickly.

The first section moves from discussing kissing's origins in nursing and premastication, looks at similar practices in the animal kingdom (moose and squirrels rubbing noses, giraffes "necking," turtles tapping heads, etc.), and ventures through cultural attitudes about kissing, from the kinds classified by the Vatsyayana Kama Sutra through The Iliad and other mythologies and on into the more than 30 different German words for kinds of kissing. It's a book filled with these sorts of random factoids, such as that in the 1950s, Dr. Owen Hendley of Baltimore City College discovered that "278 colonies of bacteria could be passed between kissers, although over 95 percent were of the harmless sort."

Kirshenbaum covers the human body's responses to kissing with a similar economy, discussing differences in male and female responses and theories about certain kissing practices from the perspective of evolutionary biology (in a 2003 study, biopsychologist Onur Gunturkun discovered that two-thirds of people tilt their head to the right when kissing, which he suggests is a head tilt preference that originates in utero while others postulate that it's a behavior learned when nursing). It may feel like Kirshenbaum is sprinting through her material sometimes, but she has done a commendable job of demonstrating how many different science specialties have produced kissing data without much cross-specialty dialogue. (For anybody who wants to do more heavy lifting, there's a 20-page bibliography with, for instance, K. Grammer's 1993 article "5-a-androst-16en-3-a-on: a male pheromone? A brief report" in Ethology and Sociobiology.)

Kissing really earns its science nerd stripes, though, in its third section. Kirshenbaum sets up an actual experiment to see if any new ground can be broken. She enlists New York University cognitive scientist David Poeppel and a magnetoencephalography machine to study brain activity during kissing. The actual results are less illuminating than the experiment construction: Science didn't have an "official taxonomy of kisses," meaning there would be nothing with which to compare gathered data, and two heads couldn't fit inside the machine comfortably, meaning the very measuring apparatus would influence the results.

Even when Kirshenbaum and Poeppel believed they had arrived upon a good model for the experiment, they came across certain variables that indicated there were things they could measure accurately and those they most definitely could not. Did they break any kissing ground? Not really, but as often happens in science, the journey to seeing what you don't know is as educational as the observable phenomenon. The Science of Kissing is an entertaining and informative read about a practice that we should all spend more time investigating.