Artist who created controversial Detroit Institute of Arts 'pro-cop' painting says she regrets it

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

The Detroit Institute of Arts drew backlash over the weekend after it posted photos of a new public work of art it created for the Sterling Heights Police Department that critics say showed poor taste and timing considering the growing movements for Black lives and police reform.

The painting, titled “To Serve and Protect,” depicts police officers holding hands in prayer against the backdrop of an American flag. “Did our taxes fund this pro cop mural?” a group of museum employees called DIA Staff Action wrote on Instagram. Others accused the artist who painted it, Nicole Macdonald, of being a white supremacist. The museum responded to the backlash by removing the post, and then creating another post explaining that it removed the post due to the “tone” of the comments. It then deleted the second post as well.

“I’ve never received this kind of reaction,” a dispirited Macdonald tells Metro Times. “I feel totally destroyed.”

Macdonald says the backlash against the painting especially hurts because she, as a white woman who grew up in the majority Black city of Detroit, has dedicated much of her artistic practice to celebrating the city’s Black history and interrogating Detroit’s redevelopment. She has created a series of murals based on people who have largely been written out of history featured in Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, and another celebrating historic figures from Detroit’s African American Black Bottom and Paradise Valley communities. As a filmmaker, she has created a documentary about how the city’s scramble to host the 2006 Super Bowl led to it demolishing derelict buildings that she considered architectural gems.

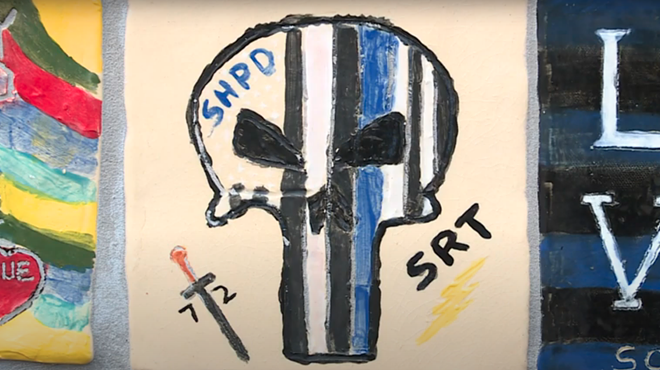

Macdonald says she was recruited to work on the mural by the museum’s Vito Valdez, who helmed the creation of a space on the wall below the painting that includes ceramic tiles created by police officers and their families. Other comments on social media criticized the museum for including tiles featuring the “Thin Blue Line” flag and the Punisher logo, a symbol gleaned from a violent Marvel vigilante antihero. Critics say both symbols have become co-opted by extremists and hate groups.

A museum spokeswoman tells Metro Times it deleted the posts “out of concern for individuals who were being personally targeted in the comments.”

“To Serve and Protect” — not technically a mural, since it was not painted directly on the police station’s wall — is a reproduction of a smaller painting created by Macdonald in 2018 as part of the DIA’s Partners in Public Art Program (PiPA), which was designed to bring art to the metro Detroit communities that support the museum with a millage tax. As stipulated in the millage terms, which voters approved in 2012 for 10 years and renewed in 2020, members of the communities that support the DIA can request the museum to create public art projects for them. For “To Serve and Protect,” Sterling Heights Police Department provided feedback and input on the final design.

“Like all PiPA projects, the artist designed the mural based on input from the specific community that requested it,” the museum spokeswoman says. “As outlined in the contracts that the museum has with each county that provides funding to the museum for these projects, community partnerships like PiPA must ‘respect and sustain the mission of the local organization and preserve the local character of each program.’”

The spokeswoman adds, “A broad and diverse region supports the DIA with millage funds, providing more than two-thirds of our operating budget. As a consequence, individual communities will have priorities that differ greatly from others.”

Macdonald says she regrets taking on what she now describes as a “bad assignment.” Her initial sketches were in a different direction, with one showing a police officer embracing a young Black girl.

Another sketch was a version similar to the final, but without the American flag. The flag was added with input from the police department.

Macdonald says her intent was to create a painting with a message about police reform showing “humility and introspection and peace,” she says, adding that she is a socialist who supports the Detroit Will Breathe anti-police brutality movement.

“I was trying to do something where they were like in a peaceful moment, like a humble moment,” she says. “And then they had me put an American flag in the background, and I’m not very pro-American, either.”

She adds, “So people are now saying that it’s like bowing and praying in front of the flag, which is just gross. I mean, I understand the reaction.”

Now Macdonald says she believes the painting should be taken down.

“I sort of feel like they should,” she says. “I mean, I can’t make that call, but at this point I kind of feel like that, because I think that art should serve the public if it’s public art, and the museum is in a majority Black city. And if people find it to be a reflection of hostility, that is not my intention — it is absolutely, 100% opposite my attention.”

She adds, “I was trying to send a message of humility and reform to the police department. If that wasn’t executed in and of itself … If a picture of the police reads as police brutality, then it should come down.”

Macdonald, who was born on the east side of Detroit and grew up in the city, says she has always identified as a Detroiter. “It’s like my culture too,” she says. “I mean, maybe that doesn’t sound right, but that’s the way I feel. And I’m interested in that history. I’m not interested in, like, Irish history. I don’t know why, I’m just not. I’m interested in where I came from, and I want to pursue that in my work.”

On Instagram, Macdonald was defended by Sabrina Nelson, a Black woman and artist who also works at the DIA, who said Macdonald was “not a little lost white girl from the burbs, she’s a super good artist and often does murals of education folks or freedom fighters who are from the city and mos definitely Black. I think it’s horrible how she’s being attacked.”

The controversy comes as the DIA has faced calls from DIA Staff Action for the ouster of museum director Salvador Salort-Pons over allegations of a toxic workplace, including instances of racial insensitivity and nepotism. An investigation conducted by a law firm hired by the DIA found that Salort-Pons presided over an “autocratic” culture at the museum that saw women quit at higher rates than their male counterparts, including a Black woman who resigned because she felt she was “tokenized,” and Andrea Montiel de Shuman, a Mexican American and the museum’s former digital experience designer who resigned in June 2020 after she felt the museum did not do an adequate job of contextualizing the colonial racism and sexual abuse surrounding a Paul Gauguin painting that depicted his 13-year-old Tahitian “wife.”

In September 2020, the museum announced it hired Kaleidoscope Group, a Chicago-based public relations firm, to lead an Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility (IDEA) project as part of an initiative dating back to 2015 to help the museum with social justice issues.

But the museum has faced backlash in recent months for other perceived instances of insensitivity in social media posts.

In November 2020, the museum drew ire when it posted a photo on its Instagram account depicting a sculpture of an Algerian woman by the French artist Charles Cordier in 1856. “In an earlier version of this post, this caption gestured towards Cordier’s admirable intentions in studying the diversity of creative production beyond European borders,” the now-edited caption reads. “Unfortunately, the post did not probe the long and violent history of colonialism. France colonized Algeria from 1830 until 1960, brutally exploiting the local population under their military rule. This troubling history necessarily informs one’s understanding of Cordier’s elegant sculpture, and we apologize for not framing the work in this complicated context from the outset.”

The museum added, “When grappling with the complicated reality of sculptures like these, the hope is that it will stage open-ended conversations about the influence of Algerian culture on the canon more broadly.”

Then, on Sunday, the museum posted a photo of the work of artist Titus Kaphar but declined to credit him in the caption, instead crediting the wealthy collectors who loaned the piece to the museum.

“EDIT YOUR CAPTION AND CREDIT THE BLACK ARTIST WHOSE ARTWORK IS REPRESENTED IN THIS LAZY ASS POST,” artist Kevin Beasley wrote in the comments.

As the winds of cultural change shift toward a demand from audiences for more critical analysis and contextualization of artwork and the systemic racism that surrounds it, the museum will have to reconsider how it presents its work — and who it works with.

“Since 2018, the year this mural was painted, much has transpired in our country and we understand and respect that many members of our community are hurt and angered,” a spokeswoman says of “To Serve and Protect” in a statement. “To support healing, we will continue investing in partnerships with community-based non-profits in the tri-county region led by and serving the BIPOC community.”

Macdonald says she’s also doing some soul searching.

“The DIA and all these institutions need to be looked at in terms of who they privileged, and who they have presented, and all of the aspects of capitalism, and globalism, and imperialism that informed that,” she says. “And, you know, I’m a product of that, too. Just like people have to reckon with their white privilege, or if they want to be an antiracist as the book says, you know, it’s an ongoing effort that you have to examine yourself. I hope that I will be able to examine myself as an artist, and it might be painful, but come out better.”

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Reddit.