Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Photo courtesy Camilo José Vergara

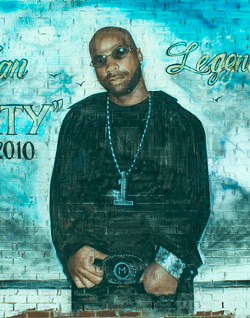

As this photo illustrates, Detroit's sign painters have a knack for creating can't-miss optic appeal that predates the coolness of "street art." But why aren't they news? Should they be?

Why did he contact me on this Monday morning? It was a piece in the Detroit Free Press entitled “Artisanal signs of Detroit's renewal, painted by hand.” I’d seen it briefly, scanning the weekend’s headlines. It’s a fairly long and loving portrait of two U-M-educated sign painters who studied the art in sunny Los Angeles. They run their quirky “hand-painted sign” business, Golden Signs, from their apartment in a nearby coastal resort community.

In short, it’s precisely the sort of thing that can get Vergara’s goat.

“This piece epitomizes so much that is wrong with a coverage of Detroit. What is admirable is produced by whites, based on a white artisanal tradition. This ignores strong, deeply rooted local black traditions.”

Vergara refers to the businesses the duo has worked for — Green Dot Stables, Third Man Records, Ottava Via, Shinola — and points out, “No storefront churches or car washes among their clients.”

Camilo José Vergara

“They’re young, they’re professional, they’re very good at what they do,” Vergara says, agreeing with the article, but adds, “and they’re working in a city called Detroit, and there’s a context, and that context should be mentioned at least in one sentence.”

Well, the article does point it out, describing what the duo does as “a nod to Detroit’s legacy of handmade signs,” and shows the twosome found inspiration in “the historic signs lining Detroit's streets.” But it doesn’t mention the obvious: Most of those murals were done by working-class black artists who did the work without charging a lot or using words like “artisanal.”

Now, nobody can question Vergara’s affection for Detroit. His upcoming book, Detroit Is No Dry Bones, comes out this fall on University of Michigan Press. He’s been coming to Detroit since 1968. And when he sees a long weekend piece on two white signpainters, or the flurry of coverage that was afforded the painting of murals in Eastern Market by street artists, a fair amount of whom were globetrotting out-of-towners, he starts to ask some hard questions.

Of course, it is news when dozens of international artists come to town and paint here. But Vergara faults the media for not diving in and discovering how rich the history of wall art is in Detroit.

He’s careful to point out that the artists are doing nothing wrong, and that their work is way above average in quality, but the problem is what is being missed, what is not celebrated: “All this stuff that’s been created by people who were getting paid maybe $200 or $300 to do a sign in a storefront church or car wash." For many years, he says, “Detroit culture has been produced in black neighborhoods, and this new movement completely ignores that.”

Sure, some of that culture gets its media close-up: But Vergara says that for every Tyree or Dabls, there are dozens more artists worth looking at.

Photo courtesy Camilo José Vergara

Art rooted in the local experience of Detroit's black community

What Vergara sees is two parallel worlds that don’t talk to each other, and artists who come to town bypassing the local tradition. That work should be seen, though, and Vergara asks how much of Detroit is being relegated to nonexistence.

But isn’t that the same everywhere? Vergara disagrees, saying, “I don’t think African-Americans are undergoing a situation similar to Detroit anywhere in the country.”

All that qualification and devil’s advocacy aside, I’m sympathetic to Vergara’s cavils. I’m happy to add that Metro Times has generally jumped at the chance to feature vernacular artists, as when Dirk Bakker allowed us to use imagery of hand-painted signs 13 years ago, or when we got a chance to speak with Sylvia Burke about her one-woman crusade to immortalize Detroit history, or when we reviewed David Clements' book on the city's "commercial folk art," or when we got to feature the late Hermon Weems, who had done everything from major album covers to signs for local businesses, or to cover Vergara's own work on hand-painted religious imagery over the years.

To help make his point, Vergara offers a few paragraphs from his forthcoming book:

Wanting to get far away from ruins and desolation, Detroit sponsors upbeat artists. In strategic locations, such as Michigan Avenue and Grand River Avenue northwest of the Michigan Central Station, cheerful murals “change that ruin porn narrative.” The murals are made with corporate support and curated by galleries. Challenging decay with images of “magic,” flamboyant imagery—such as castles, sharks, and dragons—artists encourage developers to follow their lead and rebuild the city.

In contrast to these commissioned murals are the folk images that I collect from the distinct culture of black, segregated Detroit. In no other large American city has segregation been so extreme and lasted for so long. Nowhere else is the black population so homogenous. As a result, struggling neighborhoods here contain a concentration of Afrocentric commercial and religious imagery, naive folk signs that are simple and impervious to fashion. This huge body of street art constitutes, I believe, the purest expressions of what it is like to be African American, segregated and poor.

What Vergara seems to be asking is, in this context, which body of work is more special? Which is more precious? Which deserves more discussion and which demands more scrutiny?

It’s a fair point, one we put out to our readers.