Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Jim Coleman

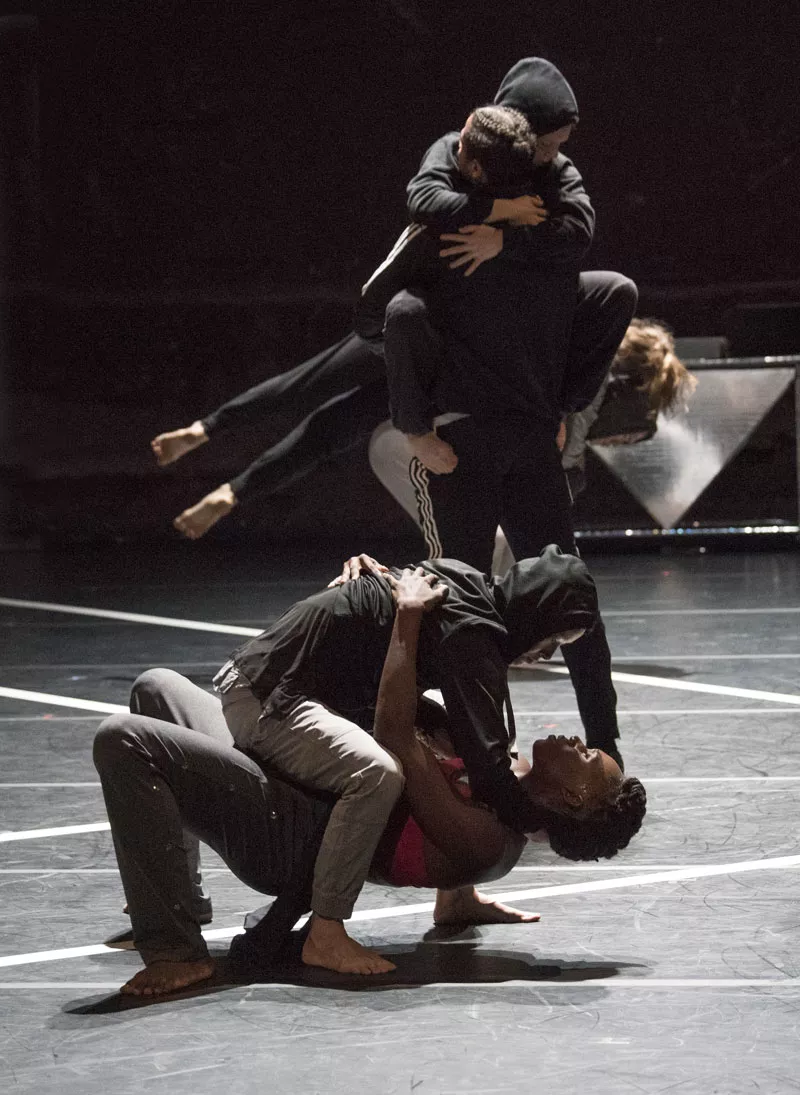

Fog or smoke seeps onto the stage, and the cast of 9 dancers dress in track pants, flannels, and hoodies. They could be anyone at the corner of Gratiot and Mack avenues as they parade out and posture at each other. The tension builds as they mold into solid, combative stances. With a loud slap to a girl’s face, the tension erupts in violence. Fists fly, legs hurtle, bodies are tossed and tumbling. The chaos halts with a piercing cry.

Jim Coleman

A Letter to My Nephew, in all of its iterations, has been site-specific. While the choreographed movement remains the same, for each city it is performed in the text and imagery is customized and projected onto the white square throughout the piece. References to Detroit are featured throughout. An image of Michigan Central Station at the back of the stage flickers as though under a strobe light. A picture of a car on fire is illuminated, recalling the riots (or rebellion) of ‘67. Jones’ recollections of Detroit from his youth include the failing auto industry to fantasizing about being Berry Gordy’s next headliner. All of this amid a democracy of movement styles; sashaying and posing from the underground vogue ballroom scene of New York, the wobble, hip-hop, and the pulsating substance-fueled rhythms of club kids dancing.

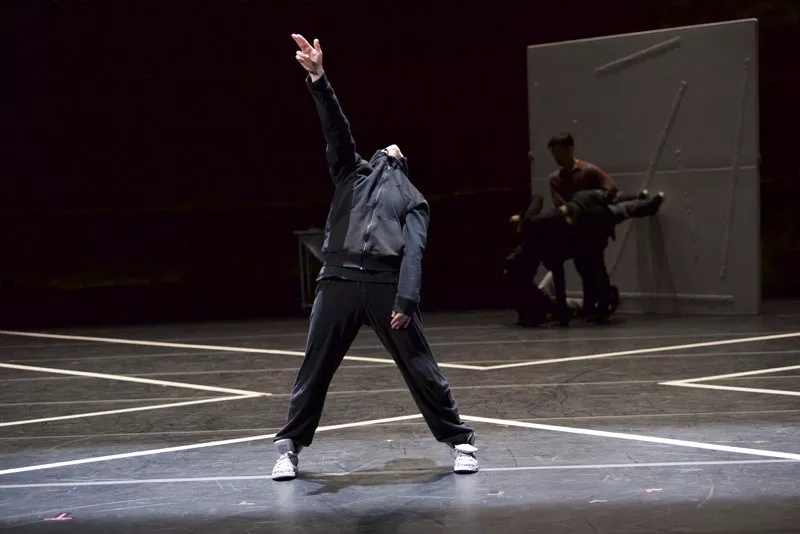

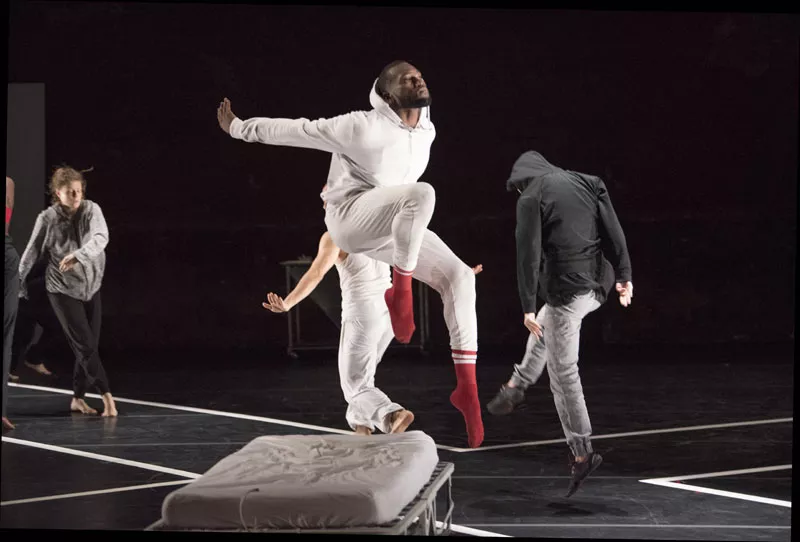

White tape outlines a large X on the stage where a procession ensues. Some strut through in stilettos as though modeling on a catwalk, others hobble along at a low level with their hoodies hiding their faces. They appear desperate and searching, perhaps junk sick. One club kid strikes a pose in a wide-legged step, arms up proudly in a V. Is it an invocation or a declaration? A character in white sweats and red socks, the nephew, is held up by others as his legs give out from underneath him. He is assisted to a clean white hospital bed on wheels and left alone, bedridden. The bed remains ever-present, a reminder of his illness.

Jim Coleman

We hear the national anthem and watch as a dancer kneels front and center stage. Violence, poverty, the health care debate, addiction, incarceration, the Black Lives Matter movement – it’s all laid out on the table for us to examine. Projected onto the letter Jones asks, “Do you feel safe?” “Did you vote?” He implores us to “Keep fighting.” Later, a personal message from Jones to Briggs reads, “Your doctor was unsure if you would live but like this town, you rise.”

Jones pointedly asks us to make connections between our beloved city’s history and our national story through his family’s narrative. How are the headlines seeping into our daily lives and into our bodies? What do we do about it? In the face of our national crises, we all could use a respite to a sunny, tropical locale. But, sometimes all you get is a postcard.

Get our top picks for the best events in Detroit every Thursday morning. Sign up for our events newsletter.