Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Let's get this out right from the start: News Hits has a hard time being even close to objective when it comes to covering the legal tussle going on between Detroit Free Press reporter David Ashenfelter and former federal prosecutor Richard Convertino.

We don't like to see good journalists called criminals for essentially doing their jobs. If reporters routinely fear prosecution for providing an otherwise absent watchdog role over government, everyone suffers.

Think Kwame Kilpatrick.

But part of us does understand Convertino's position of wanting the truth to come out relevant to his personal lawsuit against the government. We've seen the movie Absence of Malice many times, and get the concept of unnamed government officials unscrupulously using the press as a weapon against someone they're out to get. We also understand how frustrating it can be for the aggrieved person trying to find out exactly who leaked the tar so that they can be held accountable. All of which is part of the reason we find the case fascinating.

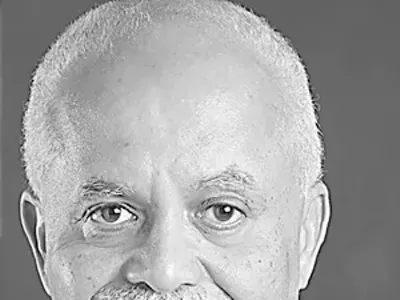

Convertino, now in private practice in Plymouth, has filed a whistle-blower lawsuit against his former employer, the U.S. Department of Justice. Among other things, Convertino claims an unnamed official illegally gave Ashenfelter information for a 2004 article about the department investigating Convertino's handling of a high-profile terrorism trial.

Convertino also claims he was punished for complaining — to Congress, in fact — about a lack of resources to fight terrorism.

Now, as discovery in his civil suit progresses, Convertino is trying to force Ashenfelter to disclose his source. So far, U.S. District Court Judge Robert Cleland has sided with Convertino, twice ruling last year that Ashenfelter would have to testify under oath.

But Ashenfelter and his legal team threw a wrench into the works at his Dec. 8 deposition by refusing to answer certain questions, claiming Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination.

Ashenfelter and his lawyers say that just the possibility he could face criminal charges related to what he might say under oath is enough to justify taking the Fifth when refusing to answer questions.

In a court filing last week, Ashenfelter and his attorneys argued that he has a "legitimate basis to fear prosecution in connection with the confidential documents and information that Convertino alleges Ashenfelter obtained and published."

At times, Convertino has made the argument for him, saying (as paraphrased in Ashenfelter's court filings last week) there are "conceivable options for prosecution" of the reporter. But Convertino's attorney, Steve Kohn, tells News Hits that the Fifth Amendment claim is "frivolous." A Department of Justice investigation years ago did not target Ashenfelter, Kohn says, so there's no reason to worry about charges now.

"It's far more likely he will be struck be struck by lightning than face charges, yet he still leaves his house every morning," Kohn says.

Convertino is now seeking to have Ashenfelter held in contempt and fined up to $5,000 a day for not answering the deposition questions.

Richard Friedman, a University of Michigan law professor, called the Fifth Amendment tactic "good lawyering" that could work for Ashenfelter.

In civil cases, he explains, plaintiffs like Convertino do have a right to gather evidence. And "just because somebody is a reporter doesn't put that person beyond the reach of the law," Friedman says.

But the right to avoid self-incrimination may take precedence. "If Ashenfelter's really got a Fifth Amendment privilege, I don't think there's a constitutional right of the plaintiff that would trump it," says Friedman, who teaches civil procedure and constitutional law. "The Fifth Amendment privilege is just tough luck for the person who wants the evidence. In any criminal action, if we didn't have the Fifth Amendment it would be easier to prove."

It's tricky. Nowhere in Ashenfelter's arguments does he admit to criminal activity. But he lists a number of justifications for invoking the Fifth Amendment: If his sources were prosecuted for conspiracy, for example, he could also be prosecuted. Ashenfelter also cites case law that permits people to invoke the Fifth Amendment if they "can imagine the possibility" of being prosecuted if the sought-after information is released.

It's not a stretch that testimony in a civil case could lead to criminal charges, says Christopher Peters, associate professor of law at Wayne State University. "It happened to Kwame Kilpatrick," he says. The former Detroit mayor and his former chief of staff, Christine Beatty, are both serving time for perjury charges — their testimony in a civil case contradicted what text messages obtained by and published in, ironically, the Free Press, showed.

"That's why the Fifth Amendment applies in civil proceedings, because it's possible that if you say something that incriminates yourself, you can be prosecuted for that and there's that evidence against you," explains Peters. "After all, what could be better evidence than something you said under oath in another proceeding?"

In addition, Ashenfelter argues, the last three U.S. attorneys general have publicly said reporters who published confidential, terrorism-related information, as Ashenfelter did, could face prosecution under the Espionage Act. Other federal statutes including the Privacy Act, he says, "criminalize the improper receipt and distribution of confidential government documents and information."

In the brief, his attorneys write, "Mr. Ashenfelter's fears are not fanciful, they are quite plausible. For that reason alone, the Court must uphold his assertion of the Fifth Amendment privilege."

But Cleland will have to decide. "Judges don't have to take you at your word when you plead a privilege," Peters says.

A hearing is set for Feb. 11.

The Convertino-Ashenfelter dispute is part of the lengthy fallout from a federal criminal case that began with the first arrests of alleged terrorists after Sept. 11. Six days after the 2001 attacks, federal agents nabbed three men — and later a fourth — who were living in a southwest Detroit apartment thought to be the former home of an alleged al-Qaeda operative.

Convertino, as the lead federal prosecutor, tried the case in 2003, accusing the four men of operating a "sleeper cell" that, among other things, planned to attack an air base in Turkey. One man was acquitted, another was convicted only of document fraud and two were convicted of conspiring to support terrorism and document fraud.

But at the end of 2003, U.S. District Judge Gerald Rosen, who had presided over the trial, ordered a review after he learned the prosecution had documents that were not turned over to the defense.

A month later Ashenfelter reported that the U.S. Justice Department had started an investigation into Convertino. He cited officials who spoke on the condition of anonymity, fearing repercussions.

A month later, then-Attorney General John Ashcroft appointed a special attorney to investigate Convertino. Later that year Rosen overturned the "terror trial" convictions in a case widely cited as a textbook example of prosecutorial excess.

Convertino resigned as a federal prosecutor in 2005. In 2006 he was indicted on obstruction of justice and other charges for which he was eventually acquitted. Convertino sued the U.S. Department of Justice in the whistle-blower and privacy case filed in 2004 that's now held up by the battle for Ashenfelter's testimony.

In August, Cleland first ordered that Ashenfelter be deposed, a directive the Free Press asked in November that he reconsider. Cleland has cited the lack of a federal shield law that would prevent Ashenfelter from testifying. Federal courts have been divided on the issue with the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in Cincinnati, the next level up from Detroit, holding that reporters do not have a First Amendment privilege from testifying.

The U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill last year that would have created a federal privilege for reporters, but debate stalled in the Senate. President Barack Obama, as a senator, supported it, as did every senator and representative from Michigan.

In his first few days in the White House, Obama did not specifically discuss a federal shield law, but he did make bold moves showing whatever War on Terror campaign he might lead will have vastly different tactics than the former president's: ending torture as an interrogation tactic and closing Guantanamo, for example.

The three attorneys general Ashenfelter cites in his brief who discussed prosecuting journalists for publishing confidential government information were Bush appointees who have been widely criticized for their politicizing of the office. Obama's Justice Department presumably will be different.

But Herschel Fink, Ashenfelter's attorney, says national politics should have nothing to do with his client's motion to invoke the Fifth Amendment. "Political climates change with the wind," Fink says. "A witness simply doesn't have to testify at any time in a way that would lead to prosecution or provide a step to prosecution."

News Hits was written by Sandra Svoboda. Contact her at ssvoboda@metrotimes.com or