Is Charlie LeDuff really a philistine, or one of the savviest media personalities of our time?

American idiot

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Charlie LeDuff is in the news again.

The Fox 2 reporter is, of course, on the news, and has been since he took that post in 2010, but his particular brand of on-air performance art tends to blur the line between reporting the news and being the news.

This time LeDuff didn't set out to make a story, but he found himself at the right place at the right time — a nifty little habit of his — on Monday, May 18, when he was talking to American Coney Island owner Grace Keros outside of her restaurant.

A passer-by bumped into Keros as two of Detroit's most famous people chatted, snatching her cellphone out of her back pocket in the process. Keros yelled. LeDuff bolted after the thief, lurching his lithe 49-year-old frame in pursuit down Lafayette Boulevard before catching up with the culprit and tackling him to the ground.

LeDuff recounts the story to me the day after a segment on his heroics aired on Fox 2, offering some details that didn't make air, like this nugget: As the alleged perpetrator lay handcuffed on the side of the street, LeDuff got down at eye-level next to him and delivered a stern message.

"I took my sunglasses off, and I told him to remember my face," LeDuff says. "I told him, 'You don't mess with Charlie LeDuff!'"

By any metric, LeDuff stands out. He's a local reporter who doesn't look like a local reporter, eschewing the standard-issue industry ensemble of perfectly coiffed hair and suits for a slightly unkempt dark mop, goatee, and signature pair of cowboy boots, hand-painted with an American flag design.

Instead of the ubiquitous and familiar Midwestern lilt beaming from TVs across the country, LeDuff talks like a layman with an unplaceable accent that betrays his metro Detroit roots — it's somewhere between New York tough guy and vague Southern drawl.

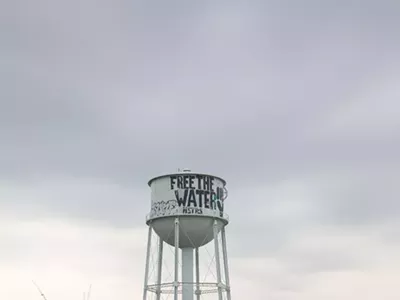

And when you watch a LeDuff segment, you instantly know it's a LeDuff segment. He's eaten cat food to illustrate Wayne County's abysmal Meals on Wheels program — a link to that segment on Reddit is titled "This guy is a reporter on Fox 2 here in Detroit. His name is Charlie LeDuff. He is fucking awesome." He's also golfed a stretch of Detroit to prove how empty it is, squatted in a house occupied by a squatter, and canoed down the polluted River Rouge. The intersection of news and entertainment has propelled those local video segments beyond metro Detroit and into the viral ether of the shareable news economy, the city itself as much a character in his segments as LeDuff.

When he returned to the city in 2008 to take a job with The Detroit News, he did so in part so that he could raise his daughter among extended family. But, as he wrote in his best-selling book, Detroit: An American Autopsy, he also came back because he thought Detroit would be the Next Big American Story. He was right. The national spotlight would soon focus on the city as the Kwame Kilpatrick scandal unfolded, the Big Three were bailed out, and the largest municipal bankruptcy in history went down. Detroit, to LeDuff, was something of a poster child for the economic malaise and racial tensions sweeping the nation.

And the nation tapped LeDuff as a sort of unofficial ambassador for the city in the process (or maybe LeDuff thrust himself on the stage). His best-seller helped, of course, as well as appearances on The Colbert Report and Real Time With Bill Maher to promote it. But Fox also took his oddball brand of reporting national in 2014 with The Americans, a segment syndicated to Fox stations across the country. And earlier this year, he became a regular contributor for Vice.

Which leads to the question of how LeDuff represents Detroit, and what he says about the media.

During a 2013 episode of Anthony Bourdain's food and travel show, Parts Unknown, LeDuff introduced the city to Bourdain as "post-apocalyptic, except for the fact that there's several hundred thousand people living here." Later in the episode, while discussing gentrification over dinner in an upscale pop-up, LeDuff spiked his soup with gin.

"Charlie LeDuff may have a Pulitzer Prize, but his appreciation of fine food and dining is, shall we say, lacking," Bourdain says in a voiceover. "Simply put, he's a philistine."

The first time I crossed paths with LeDuff was in a bar in Ferndale — his cowboy boots a dead giveaway. I nudged my girlfriend: "I'm pretty sure that's Charlie LeDuff."

My girlfriend recalled that her dad was a fan, and after we finished our drinks, we asked LeDuff for a photo.

I introduced myself as a Metro Times writer — and instantly winced, recalling that LeDuff was the subject of a critical MT story a few years ago. It centered on one of his most memorable and disseminated stories, a 2009 above-the-fold News piece titled "Frozen in indifference: Life goes on around body found in vacant warehouse." A four-column-wide photo of a dead man's legs sticking out from ice topped the article. Then-Metro Times news editor and current MT contributor Curt Guyette dug into the macabre tale of a dead homeless man and a basement hockey game and discovered omitted and sensationalized details in LeDuff's report.

The follow-up, "Anatomy of a Story," demonstrated LeDuff's propensity for making himself part of the news he covers. It wasn't that LeDuff got the story wrong — it was the nuance of the backstory that left some looking for more context. Either way, LeDuff was not pleased. Chances were good he was still not pleased.

Plus, I remembered LeDuff's tempestuous reputation otherwise — he was alleged to be involved in a St. Patrick's Day brawl in 2013 — and began to wonder if maybe this was a terrible idea after all.

But, thankfully, LeDuff shrugged the MT thing off and agreed to pose for a photo, but only if my girlfriend called her dad so he can talk to him.

"Hello?" LeDuff said after she put him on the phone. "You're speaking to Charlie LeDuff." The two engaged in a lengthy conversation. The bar was loud enough that we couldn't hear what LeDuff was saying, but he seemed to be enjoying the attention.

After the photo, I asked LeDuff about writing even after he'd made the transition to television personality.

"I like writing better," he said. "But it's hard to get people to read."

The line sticks with me, and weeks later I call LeDuff's office line to talk more about the art of journalism and his history for a profile in this rag. Affable and approachable at the bar, LeDuff is apparently hard to get ahold of on the phone.

"Hi, You've reached Charlie LeDuff," the pre-recorded voicemail message says. "Due to the volume of calls, please do me this favor: First state your name, then your number, and in one or two clear and very specific sentences tell me what's happening — and please forgive me, chances are I won't call you back; I just can't handle it all. But, I'll try. God bless, and bye-bye."

The CliffsNotes version of how LeDuff got here: He grew up with a mother, stepfather, three brothers, and a sister on Joy Road in Livonia. His mother worked in a flower shop on Detroit's east side. His stepfather left the family. His siblings dropped out of school. His sister occasionally worked as a prostitute and died after jumping out of a speeding van and hitting a tree.

As a writer, LeDuff's big break came when he got in at The New York Times on a 10-week minority scholarship (LeDuff is one-eighth Ojibwe). That turned into a 12-year career at the paper, where LeDuff cultivated a sort of blue-collar, everyman appeal, covering the hard-working and royally screwed.

The Pulitzer Prize comes from his 2000 contribution to a 10-part New York Times series called "How race is lived in America," in which LeDuff reported on race relations in North Carolina by embedding himself as a worker for a story titled "At a slaughterhouse, some things never die."

Often, his prose read more like hardboiled pulp fiction than sterile news copy; critics call it purple, or at times, "hackneyed." Still, his populist approach was well-received by readers, even if contemporaries and his editor weren't sold: "And at the Times, it is not the reader who matters so much," he wrote in American Autopsy. He quit while on paternity leave from the Times' Los Angeles bureau.

He came back to Detroit and enlisted at The Detroit News, where he would work for two years. (According to American Autopsy, LeDuff says he quit the News when his editors watered down a critical story about a judge in his coverage of the murder of Aiyana Stanley-Jones in 2010. LeDuff later published the details in a longform story for Mother Jones.) Back then, before video made Web-reporting what it is today, LeDuff was exploring the possibilities of the medium and doing LeDuff-type things.

For an early video assignment, he sat down with then-Detroit City Councilwoman Monica Conyers, notorious at the time for freaking out during a meeting and calling then-Council President Ken Cockrel "Shrek." In the clip, LeDuff asks Conyers point-blank if she is insane.

"If you were a nut — if you were a nut," he asks, sounding like a mock lawyer, "what kind of nut would you be?" He offers some suggestions: Pecan? Walnut?

"I'd be a peanut," he deadpans.

Conyers, apparently sufficiently disarmed, asks LeDuff why he would be a peanut.

"I like peanuts," he says. "Nobody doesn't like a peanut."