Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Metro Times archives

That much is certain.

What remains a matter of much dispute is exactly how Crenshaw’s attempts to get cash that night in a rundown neighborhood ended with him slumped on the pavement of a bank parking lot, blood oozing from bullet holes in his hand, neck, side and chest.

It could be that Crenshaw, a 46-year-old factory laborer, made the near-fatal mistake of trying to rob the cop and another off-duty police officer while they were trying to make a withdrawal from a drive-up ATM on Detroit’s west side.

That is what Officer Jerold Blanding who did the shooting, says he thought was happening that night.

The other explanation is that Crenshaw’s only mistake was to open the wrong car door after making a withdrawal of his own, and that a panicked police officer began blasting away at an innocent man.

If that version is to be believed—and there are both witnesses and evidence that support it—then the key question becomes what, if any, action should be taken against the officer in such a case?

There are several possibilities.

Following a complete and thorough investigation, the department might rule that Blanding—now 30, and a six-year veteran of the force at the time of the incident—reasonably feared for his life, fired at a suspected fleeing felon and that the shooting was justified. Or, he could be found in violation of department policy and reprimanded, suspended or demoted. He could even be fired. The prosecutor’s office, after reviewing the department investigation, has the option to press criminal charges and, if convicted, he could end up behind bars.

Or he might work for a department that looks the other way when one of its officers shoots an unarmed citizen, a department that slacks off when investigating one of its own and then fights any subsequent efforts by others to uncover the facts.

Is that the kind of Police Department Detroit has?

Chief Benny Napoleon, who was at the scene, according to a report of a police officer who responded to the shooting, won’t say.

“Upon the advice of counsel and because of pending litigation I have been instructed that I should not grant the interview that you request,” said Napoleon in a recorded phone message he left with the Metro Times. “I have no problem giving it, but the legal counsel for the city said I should not grant that interview.”

Questions faxed repeatedly to the chief asking about overall policies and procedures relating to all use of deadly force by police officers went unanswered. Napoleon also did not say whether or not the department disciplined Blanding after it investigated the shooting.

The chief isn’t the only one refusing to talk about the Crenshaw case. Officer Blanding and the city attorney representing him in the civil suit brought by Crenshaw refused to comment, saying it was against department policy. Crenshaw and the woman with him the night he was shot, Glenda Webb, likewise refused to comment. Even their attorney, David Robinson, of Southfield, isn’t saying much.

After initially cooperating with the Metro times on another police shooting case he is handling, Robinson clammed up when it came to Crenshaw. He explained that the Detroit Free Press is working on a police shooting story of its own.

And Robinson, himself a former Detroit police officer who has launched more than a half-dozen wrongful shooting suits against the department in recent years, didn’t want to do anything that would jeopardize the impact that can come when an issue as important as this is splashed across the front page of a major metropolitan daily. And this comes at a time when the national media have turned the country’s attention to this issue with its coverage of the Amadou Diallo shooting by New York City police officers and the perjury and corruption scandal at the Los Angeles Police Rampart District.

The way Robinson sees it, this case is about much more than an isolated shooting. His mission is not just to win a settlement for a single client, but rather to generate enough heat to force change in a department he claims fosters policies that lead to officers using deadly force when it isn’t warranted, and then walking away unpunished. And why wouldn’t he see it this way? According to the City Law Department, the Police Department investigated about 200 police shootings between 1994 and 1999. According to the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office, 45 of those shootings were fatal and the others were nonfatal. Only two officers involved in fatal shootings were prosecuted. The prosecutor’s office does not have statistics for nonfatal shootings during those years.

At least in the Crenshaw case, Robinson may be seeing results: After the Metro Times told the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office that the Police Department never interviewed a woman who witnessed the shooting, the prosecutor’s office said last week that it may re-open the investigation. And so it is that the story you are about to read is drawn largely from police reports, sworn depositions and other court documents generated by the civil suit. This is known about the Night.

The officer’s story

Jerold Blanding, an African-American police officer, was withdrawing money from a drive-up ATM machine at then NBD (now Bank One) at Joy Road and Appoline when he heard the passenger door of his blue 1999 Chevy Suburban open. He turned and saw a black man wearing a baseball cap standing in the SUV’s doorway. The man grabbed Blanding’s girlfriend, Officer Tracey Elledge, by the right arm and tried to pull her from the Suburban, according to a police report.

“Here we go,” said the man.

“What are you doing?” asked Elledge, as she pulled her arm away and hit the man with the back of her hand. She looked down and saw something black in his hand. Blanding also saw what he says he thought to be a “blue steel” gun pointed at Elledge. Elledge screamed, pulled the door shut and leaned forward. Blanding pulled his .40-caliber Glock semiautomatic service pistol from under his shirt, and without warning, fired. The first shot shattered the glass of a window on the Suburban’s passenger side.

The man ran from the vehicle. Blanding opened the driver’s-side door and set off in pursuit. As he did so, the man turned toward the officer, still holding the black object. Asked during a sworn deposition whether he identified himself as a police officer at this point, Blanding said he could not remember.

“Fearing for his life,” at about 18 to 20 feet away, Blanding fired “a couple shots” at the man, and the object fell from his hand. A woman in a minivan parked at the bank called out to the man, but he couldn’t make it to her. After a couple more steps, he collapsed. Blanding approached the man, identified himself as a police officer and told him not to move.The officer said he saw a “blue-steel gun” and started blasting…

tweet this

Blanding then ordered the woman inside the minivan to get out and told Elledge to called 911.

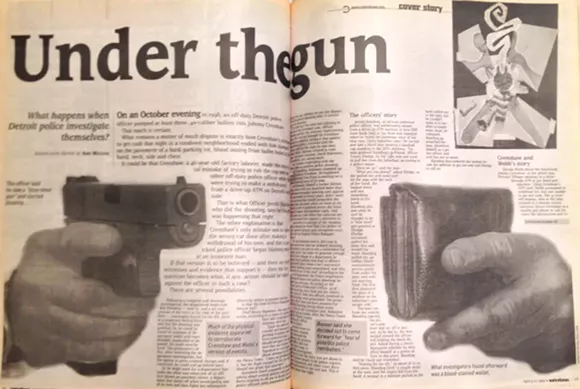

Crenshaw and Webb’s story

Glenda Webb drove her boyfriend, Johnny Crenshaw, in her green 1994 Mercury Villager minivan to a drive-through ATM at Joy Road and Appoline. Using Crenshaw’s ATM card, Webb attempted to withdraw $20, but was unable to get any cash. The 47-year-old woman, who at the time worked in a Detroit school cafeteria, drove Crenshaw to a nearby pay phone to call his sister for instructions and returned to the bank.

Again unable to make a withdrawal. Crenshaw noticed a woman in a cream-colored Contour using a second ATM. He climbed out of Webb’s minivan and asked her for help. Initially reluctant, the woman eventually agreed.

In the meantime, a dark blue Suburban pulled up behind Webb, who moved her minivan so the patron could use the money machine. She drove around the block while the woman in the Ford helped Crenshaw finally withdraw $20. As Webb re-entered the bank lot, from about 80 feet away she saw Crenshaw walk away from the Contour and, holding his wallet and cash, approach the passenger side of the Suburban where her minivan had been parked. Though Webb honked her horn and flashed her headlights, Crenshaw didn’t notice. Inadvertently, he opened the Suburban’s passenger door. “OK, Glenda, I got the money, let’s go,” said Crenshaw as he opened the door.

“Who are you?” asked the startled female passenger.

Crenshaw looked up from the wallet, money and ATM card and said, “Oh, man, I’m sorry, I thought you were a friend of mine.”

The woman started screaming, and Crenshaw closed her car door. As he walked away, the driver got out of the blue Suburban and shouted, “Hold it.”

(Crenshaw and Webb both say they did not hear gunshots until after Blanding exited his Suburban. Blanding and Elledge both say that Blanding first shot while in his vehicle.)

“I’m sorry, man. I thought that was her,” explained Crenshaw, pointing at Webb’s van.

Crenshaw continued to walk away when he heard gunfire and realized he had been shot.

“Please don’t shoot, I’m sorry,” he begged.

As he tried to make his way to Webb’s van, Crenshaw fell, face forward. Webb rushed to help him, but the armed man told her to get back to her car.

“(T)he guy pointed the gun at me and I asked him if he was a police officer. He then pulled his badge out. I asked him why did he shoot and he said he had been robbed before,” according to Webb’s written police statement.

The female passenger, also an off-duty officer, called a squad car for help. An ambulance rushed Crenshaw, who was shot in the neck, chest and left hand, to Grace Hospital where police investigators questioned him. Webb, who was taken downtown for questioning that night, said that she was handcuffed to a table for several hours before eventually being released.

The investigation

From the start, much of the physical evidence appeared to corroborate Crenshaw and Webb’s version of events.

First of all, there was no indication whatsoever that Crenshaw carried a gun that night.

What investigators did find was a trail of blood, with an ATM card and Crenshaw’s wallet, both blood-stained as well, lying on the ground. Also on the ground was a “new style” $20 bill. The obvious conclusion is that Crenshaw had been holding them, and that they were dropped after he was shot.

This would indicate that Crenshaw was either telling the truth, or he attempted to rob two people using a wallet and an ATM card as his weapons.

No charges were filed against Crenshaw or Webb. Based on the Police Department’s investigative report, the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office ruled the shooting “justified.”

There is, however, a gaping hole in the department’s investigation.

Remember the woman in the cream-colored Ford? Police records show both Crenshaw and Webb brought the encounter to the department’s attention, yet the authorities never contacted her. It wasn’t as if she was hard to find. An investigator hired by Crenshaw’s attorney tracked her down using information supplied by the bank. The statement she provided the detective is now part of the court record.

When the Metro Times showed this witness a copy of her statement last week and asked if it was accurate, Dnesi Bonner nodded her head and said, “Yeah.”

The witness’ story

Sometime around 9:30 p.m. on the night of the shooting, Dnesi Bonner borrowed her mother’s cream-colored Contour and drove to the ATM machine at Joy Road and Appoline with her two children. While making a withdrawal, she noticed a man exiting the passenger door of a van to her right. Bonner grew anxious as the man approached. It was evening after all, and the kids were with her. Nonetheless, she listened as he explained his problem and asked for help, which she eventually provided.

After finally obtaining his $20 from the machine, the man walked toward his car, concentrating on his money and wallet in his hand. She noticed that the minivan he arrived in had moved and an SUV had taken its place. As the man opened the passenger door, Bonner saw that he suddenly realized his mistake.

“The man immediately raised his hands up over his head, and began backing away yelling over and over that he was very sorry, that it was the wrong vehicle,” according to Bonner’s signed witness statement. Bonner saw the driver get out of the SUV and move toward the man, who continued walking backward with his hands in the air, screaming that he was sorry, and that he had made a mistake. When the man turned to head for his minivan, Bonner saw the driver shoot at him. Before reaching his minivan, he fell to the ground. Fearing for her children’s safety, Bonner fled.

Later that night, Bonner and her mother saw a TV news report that an off-duty policeman had shot a thief during an attempted robbery. Bonner, according to the statement, recalled telling her mother: “It was not an attempted robbery at all. The man was pleading that it was an honest mistake and the man had no reason to shoot him as he was not threatening this man at all.”

Bonner, however, decided not to come forward for “fear of possible police retribution,” according to her statement.

Prosecutor reconsiders

Why didn’t the police seek out Bonner?

Inspector William Rice, who heads the Special Assignment Homicide Squad, which investigates all shootings involving officers, told Metro Times, “The only way she would not have been interviewed is if we were unaware of her.” He then said that “there is multiple reasons why it could happen. We were unaware of her or Dave (Robinson) got to her first and didn’t give us the information.”

(Rice did not respond to repeated attempts to follow up on his response in light of Crenshaw and Webb’s account of the woman in the cream-colored Contour.)

The investigation was completed and passed on to Chief Napoleon “to do with as he pleases or sees fit,” Sgt. Reginald Harvel, a 27-year veteran who led the Crenshaw shooting investigation, said in a deposition.

After the Police Department concluded its investigation of the shooting, it provided a file containing all the evidence collected to the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office. According to Wayne County Assistant Prosecutor Robert Sheiko, who has been supervising his department’s review of nonfatal Detroit police shootings for more than two years, the prosecutor’s office depends heavily on the Detroit Police Department when conducting its investigations.

“We get the results of the (Detroit Police Department) investigation, which would be interviews of all parties, including defendants. We look at their statements and what makes sense, and make a decision based on that,” said Sheiko. “We basically rely on the investigative review of the Detroit Police Department.”

Asked if the prosecutor’s office does its own investigation of nonfatal police shootings, Sheiko said, “Ordinarily we don’t.”

There are times, however, when the prosecutor’s office may call on its own investigators or direct the Police Department to gather more evidence. But Sheiko said this is uncommon. So there was nothing out of the ordinary when the prosecutor’s office accepted the police investigation as thorough and, with no additional follow-up, determined the shooting was justified. According to a final prosecutor’s report, Blanding was “acting under belief of an attempted robbery where himself and another were in danger and attempted to apprehend a fleeing felon.”

Last week, after questions about the witness, Sheiko said the investigation may be reopened. Bonner agreed to a polygraph test this past weekend, but the prosecutor’s office would not release the results. However, the prosecutor’s office said that her statement to them was consistent with the written statement she provided Crenshaw’s attorney last year. Sheiko also said that the prosecutor’s office is going to review other information before deciding how to proceed.

More shootings

Attorney David Robinson represents Crenshaw and Webb in their lawsuit against the city, Blanding and two other officers who responded to the incident; the plaintiffs are seeking an undetermined amount of monetary compensation. Robinson says this shooting and the investigation that ensued are not unique. He alleges that investigators ignore evidence that reflects badly on their fellow officers, and as a result cops who shoot unarmed citizens are rarely prosecuted.

To back up his claims, Robinson cites court documents of a number of cases he has handled, including:

- A 1998 incident involving two officers who responded to a radio call that two shots were fired at a drug house on Roselawn. As the officers approached the home, one saw Liquory Hines inside. Both officers said that Hines pointed a gun at one of the officers. The two cops began firing, with both hitting Hines in the neck; he survived. In their written statements, both officers stated that they shot the 16-year-old because they feared for their lives. Though no gun was found, the department ruled the shooting justified and the officers were not disciplined, according to court records.

- In 1997, a Detroit officer saw Roy Hoskins carrying a nickel-plated revolver at his side. The officer said he told Hoskins to halt. Hoskins ran, and the officer chased him. According to an internal department memo, the officer shot Hoskins in the chest after the 14-year-old turned and pointed his gun at the officer. But according to the Wayne County Examiner’s Office, Hoskins died of a single gunshot wound to the back. The department ruled the shooting justified and the officers were not disciplined, according to court records.

- In 1994, Detroit officers responded to shots fired at a coney island at Woodward and East Philadelphia, where a crowd had gathered. The officers called everyone over to their vehicle. When Christopher Welch refused and walked away, one officer ordered him to halt. When Welch turned back around, the officer, “fearing for his life,” shot Welch, believing he reached inside his coat as if to pull out a gun. The department ruled the shooting justified, and the officer was not disciplined, though no gun was found on Welch, who survived, according to court records.

- In 1994, a Detroit officer was chasing homicide suspect Lamont Hemphill. The cop said he shot Hemphill because he saw a “shiny object in his hand and…fearing for my life I fired two shots.” Though the initial report the department submitted to the prosecutor’s office stated that Hemphill was shot in the chest, the Wayne County Examiners’ Office found that the bullet entered his back. No gun was found on Hemphill and the department ruled the shooting justified and the officer was not disciplined, according to court records.

In a court brief, Robinson says: “Plaintiffs have received dozens of files in discovery that demonstrate a pattern of ignoring, failing and refusing to investigate inculpating facts. No criminal or administrative scrutiny takes place.”

A spokesman for Mayor Dennis Archer, who appoints the police chief, strongly disputes Robinson’s allegation.

“This administration has a tradition of investigating all crimes to the fullest extent possible,” said Archer press secretary Greg Bowens. “If there is something suspected, it is turned over to the feds. And it is done that way so it is taken out of the blue wall in the Police Department and investigated impartially.”

An attorney such as Robinson, Bowens continued, is “going to say whatever he can to make the Police Department look as bad as possible to get as much money as possible, and that is what it is all about. Meanwhile our officers who live in the city and are from Detroit and have relatives in Detroit have a very real connection to the people they are trying to protect.”

Likewise, according to a written argument submitted to the court in the Crenshaw case, city attorney Jacob Schwarzberg contends that police shootings are properly investigated; some are ruled unjustified and officers are disciplined “whether or not the officer or citizen is injured.”

Schwarzberg also points out that disciplinary reports regarding unjustified police shootings “are distributed throughout the Police Department in order to make officers aware of the consequences associated with violating Department Rules and Regulations” and state law.

Schwarzberg wrote that Blanding “is particularly aware that he would be disciplined for improperly using his firearm since he had, prior to this incident, been disciplined for improperly discharging his firearm.

Blanding received a written reprimand in 1995 for shooting a pigeon while on duty.

According to Robinson, because the department has thus far refused to provide him with its internal report on the Crenshaw shooting, it is unknown whether the consequences Blanding faced for shooting Crenshaw were more severe or less than the punishment meted out for the pigeon incident.

That reluctance to relinquish potentially damaging information is also part of a pattern alleges Robinson. He’s not alone in making that claim.

Guarding information

“The Police Department is notorious for giving up as little information as possible,” says Diane Bukowski, a member of the Police Brutality Coalition, a group formed by self-described victims of police abuse, their families and supporters.

Bukowski relates how the group filed a Freedom of Information Act request asking for all the files involving police shootings for at least a 10-year period, only to have the request denied.

“They said they don’t keep records and aren’t required to keep records,” said Bukowski.

The department did, however, suggest that it could provide information on individual cases if the names of those involved were specified. So more requests were filed, but no information was ever forthcoming, claimed Bukowski.

The Police Department is not the only city agency that appears to be uncooperative when it comes to giving up information on shootings involving officers.

The city’s Law Department is also being criticized.

During a City Council meeting in January, some council members expressed frustration with the relationship between the Board of Police Commissioners, a citizen panel that establishes policy for the department, and the Law Department.

What makes the board’s job difficult, says chairperson Zeline Richard, is that the Law Department does not automatically make information regarding lawsuits available. Because of that, the board often finds itself unable to answer citizen questions about officers named in these lawsuits.

Council member Ken Cockrel Jr. said he found it “scary” that the board did not routinely have this information.

“To me that is, if not No. 1, definitely one of the top priorities that your body should be looking at,” said Cockrel. “It raises the whole question of why we even have a Board of Police Commissioners.”

According to the City Charter, the board—which is appointed by the mayor—does not automatically review police shootings. It becomes involved only when an officer appeals a discipline ruling or a citizen lodges a formal complaint.

Richard recently told the Metro Times that the board looked into reviewing all lawsuits involving officers from the city law department. But it seems that the board did not have much success. Richard said that the only way the board’s role will change is if the citizens vote to change the charter.

But there may be another way to address the issue. Last month, U.S. Rep. John Conyers, D-Detroit, introduced the Law Enforcement Trust and Integrity Act of 2000. The bill, if enacted, would mandate the U.S. Justice Department Office of Civil Rights to create a division that develops police department accreditation policies and investigate police shootings.

“We want to set standards that would begin to deal with the I-thought-it-was-a-gun routine,” said Conyers.

The close relationship between police officers and prosecutors who work together to convict criminals is another reason an independent investigator is needed, he said.

Back tracking“We want to set standards that would begin to deal with the I-thought-it-was-a-gun routine,” said Rep. Conyers.

tweet this

Another major shortcoming pointed to by critics is the Police Department’s failure to track police shootings.

The need for such a system was highlighted in 1997, when the City Council member Mel Ravitz, frustrated by seeing the city shelling out millions of dollars in Police Department legal settlements and unable to obtain a concise overview of the circumstances surrounding these cases, collected data on his own. He presented the findings to both the City Council and the Police Department. According to the information gathered by Ravits, the city spent $92 million on police lawsuits between 1987 and 1996. The suits involved everything from minor traffic accidents to excessive force and wrongful death cases.

“I hoped to find out what kind of pattern there was, and if there was a way, with the cooperation of the Police Department, to offset this hemorrhaging of funds,” Ravitz said recently.

What makes the lack of a tracking system especially odd is the assertion from attorney Juan Mateo that just such a system was formerly maintained by the department.

Mateo, who like Robinson handles a number of police shooting cases, told Metro Times that in the late ‘80s he obtained from the department a computer printout detailing information about 636 shootings that took place between 1982 and 1987. Included with the information was a summary of the incident and a report that contained such details as the number of shots fired, type of weapon discharged and the distance between the shooter and the victim.

When he recently requested similar information, Mateo said he was told it didn’t exist.

“They don’t want the lawyers to have it, let alone the public,” complained Mateo.

Policing the police

Regardless of how many police shootings occur in a city, each one must be “treated with a great deal of intensity,” says Joseph McNamara, a fellow at the Hoover Institute on War, Revolution and Peace at Stanford University. McNamara is considered an expert on police policy reform because of the changes he instituted while serving 15 years as the San Jose police chief before he retired in 1991.

McNamara says that when he became the chief in San Jose, police shootings seemed unusually high.

“So I put in a change that really work,” he says.

Every time an officer shot a civilian, McNamara was called to the scene.

“That sent a message that this is a big deal, that the police chief will be woken up at 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning and that is how serious it is,” he says.

McNamara also ensured that his officers receive annual training on arrest techniques and restraint holds to reduce their use of excessive or deadly force. Consequently, he says, “shootings went down, arrests went up and crime declined overall.”

To determine whether a police department has a high number of police shootings, McNamara says this information must be tracked—and made available to the public.

“I think it is one of the most important aspects of policing,” says McNamara. “The public has an absolute right to know how much deadly force the police are using.”

According to Second Deputy Chief Ursula Henry, who heads the Risk Assessment Section, the Police Department intends to track this information, as well as how many police shootings are deemed justified. She said that by doing so, the department hopes to reduce possible liability.

Asked when the Police Department is scheduled to begin tracking police shootings, Henry said, “I wish I knew.”