Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Jim Storm has an easier time than most. In the region that gave America a set of wheels, the Ferndale resident hasn’t owned a car in years, leaving behind the perpetual repairs, insurance payments and gas pumps for the bus — and for him, at least, it works.

The thought of someone actually ditching his car in metro Detroit, however, is virtually unheard of. Living within a stone’s throw of Woodward Avenue, though, it makes sense for Storm. During the week, the 43-year-old leaves his home in the morning, walks toward the Suburban Mobility Authority for Regional Transportation stop near the southwest corner of Marshall and Woodward avenues, waits for one of the numerous Woodward SMART buses — one typically arrives every 15 minutes — and rides to the Detroit Institute of Arts, where he’s worked for years as the museum’s mount designer and fabricator.

Storm knows his situation is unusual. He is the rare automobile-less alien in public transit-troubled car country.

Clutching a copy of The New York Times outside the DIA on the last day in February, Storm says of his bus route: “It works out great, I read the paper in the morning; I don’t have to worry about parking, paying insurance on a vehicle, a lot of stuff,” adding, “Thankfully, I live within walking distance to my stop.”

Of the 106,000 daily riders along DDOT’s three dozen routes, and 35,000 daily riders on SMART’S 43 routes, Storm is an anomaly — the metro Detroit transit rider who can enjoy leisurely reading the newspaper on his bus route to work. There are certainly others like him, but they’re so uncommon it’s a fool’s errand to find those who would echo Storm’s words.

Cities like New York City and Seattle have reliable public transportation, the kind of efficient, ubiquitous service that ferries commuters with few headaches besides a few grumbles about a packed bus or a temporarily closed station. But those are minor complaints, and ones many folks here would love to have in exchange for the status quo.

In metro Detroit, public transportation is a bunk concept; most riders, with no hesitation, will offer a similar refrain when asked their opinion: They hate it. It’s a sick joke; ride a bus long enough and you’d surely hear a horror story.

How’d it get this bad? Why is it that someone who wants to get from downtown Detroit via DDOT to a job at, for example, the Costco in Livonia, needs to budget two hours for the trip? When driving that route would take a mere 15 to 20 minutes? Consider the two transfers needed to make that bus ride happen, tack on the inevitable waiting period, and it begins to make sense why this region is beholden to the automobile not just by name, but in practice too.

In the case of Detroit proper, as the city’s fiscal picture deteriorated over the last four decades, its public transit has fallen in tandem. It’s an unfortunate reality for the residents of roughly 60,000 households in Detroit, of whom 80 percent are black, who have no access to an automobile.

Ask that question — why is public transportation here so unreliable? — and the finger-pointing begins: It’s the transit planners; there’s never enough funding; there’s not enough interest from the public; the divide between the suburbs and Detroit has made it near-impossible. Some bring up the General Motors streetcar conspiracy, even though it was a manager of the city’s old streetcar system who originally vowed to ditch rail for buses.

Is there a smoking gun? Most would say no, that it’s an amalgam of these issues.

The city’s streetcar system halted operations in April 1956. The web of privately owned bus systems across the region would dissolve soon after. The commuter rails that had connected Detroit, Ann Arbor and Pontiac were discontinued in the ’80s. Today, Detroit is basically left with two disconnected bus systems that generate more headaches than on-time transfers or speedy rides.

Believe it or not, metro Detroit’s public transportation was far more developed and useful in 1950 than it is today.

The city was once able to call itself the owner of the largest municipally owned street railway system. Were a rail system to be introduced today, the Southeast Michigan Regional Transportation Authority board would have to unanimously approve it, which is no small task. By contrast, only a supermajority is needed to seek voter approval for a new bus system or a rapid transit system. It’s as if Lansing scripted laws to mandate the region’s transit priorities.

In truth, Detroit could’ve easily had a more robust, efficient system in place today if decisions were made differently — even after the federal government invested heavily in the freeway system, allowing motorists to pack up and move to the suburbs. History does support some critics who blame the region’s absence of comprehensive public transportation on a lack of public interest. In some instances, it was a vocal minority choosing personal sentiments over the betterment of the region. But, some say, if the public wasn’t crying out for better public transit, it was because no one took the reins and showed them what a good system could look like.

Transit boosters have optimistically pointed to the new M-1 Rail streetcar line in Detroit as a sign of hope for the future in the region. The $140 million privately funded venture will shuttle residents and employees between New Center, Midtown and downtown. The progress heartens advocates of a more expansive system, but it remains unclear if the transit line will be tied to an economically flourishing section of Detroit, or if planners will allow for future expansion into a real rapid transit system that embraces the city limits and beyond.

All that said, the historical record shows that, had some elected officials bitten their tongues and made some tough decisions, it’s likely there’d be more Jim Storms riding public transit in our region today.

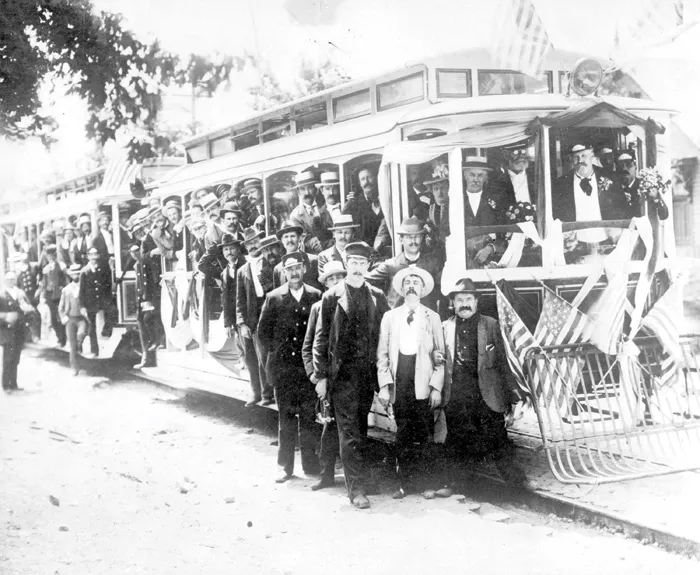

THE RISE

The average Joe in the 1910s and 1920s had choices to get around metro Detroit: Cabs, trains, an interurban, streetcars, horse-drawn vehicles, walking. Those looking to gain some freedom from the rail monopoly of the time turned to the automobile as a saving grace. It was also a major turning point for public transit within the region, beginning with the city’s shift to municipal ownership of the streetcar system in 1922.

As more residents moved outward from the city’s core, Detroit remained connected through its Department of Street Railways, with more than 500 miles of track and feeder buses.

Numerous proposals were floated to expand the system with new subway routes. In 1920, after a rapid transit plan for the region was completed, Mayor James Couzens vetoed a bond issue to construct a subway. Toward the end of the decade, as the DSR reached its apex, voters were considering another plan to construct a subway line from the city to Ford Motor Co.’s Rouge Complex. It was actually supported by automakers, as described in an article for Progressive Planning magazine by Joel Batterman, policy director for Detroit faith-based group MOSES. But the 1929 proposal failed due to reasons all too familiar for the region.

“[The subway] met fierce opposition from the homeowners’ organizations that also held the line against neighborhood racial integration,” Batterman writes. “The subway would serve the automakers and downtown businesses, they argued, at the expense of the expanding middle class, which inhabited the city’s vast tracts of new single-family homes and no longer relied on Detroit’s extensive but slow streetcar system.” Batterman cites a historian who said the proposal garnered the most support in the black ghetto, where workers needed transit to reach their jobs.

Then, the Great Depression came, striking a blow to streetcar ridership. In part to stave off rising maintenance costs, the DSR began running buses more frequently. But it wasn’t just money that served as the chief factor for Detroit’s shift toward buses. In the mid 1930s, DSR general manager Fred A. Nolan launched an effort to convert the city’s streetcar system entirely to buses by 1953.

Bus-happy Nolan reduced the system’s rail fleet from 1,600 cars in 1934 to 908 by 1943, according to Bernard Craig, a retired terminal supervisor for DDOT who maintains an exhaustive history of metro Detroit’s public transit involvement at DetroitTransitHistory.info. But Nolan’s plan didn’t last long. World War II revived the Detroit economy, rebranding the city as the Arsenal of Democracy, giving the streetcar system a boost.

“… restrictions imposed by the U.S. Office of Defense Transportation during World War II would require the use of streetcars in place of buses where possible to help conserve gasoline and rubber, resulting in the temporary restoration of full-time streetcar service on the city’s rail lines in 1942,” Craig writes.

Ridership spiked again to more than 490 million. But the increase deteriorated DSR’s rail infrastructure. The wheels were in motion to shutter the streetcar operations for good.

The city discontinued half of its 20 streetcar lines by 1949, dropping five more in 1951. At the same time, transit workers went on strike, which took another whack at ridership levels, according to a University of Detroit Mercy study. After the DSR purchased hundreds of buses to run along the streetcar routes, the rail system was made obsolete.

In April 1956, the last streetcar rolled down Woodward Avenue.

Just two months later, President Dwight D. Eisenhower would sign the Federal Aid Highway Act, authorizing the construction of more than 40,000 miles of interstate highway. Automobile costs had dropped, becoming more affordable for the average American family. It was the first warning sign that metro Detroit transit agencies had to adapt or die.

WHAT PUBLIC TRANSIT MEANS

Even Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan focused on the need for a reliable bus system in Detroit during his State of the City speech last month.

“A job [in Detroit] means a reliable bus system,” the mayor said, before highlighting the tribulations of one resident who travels to Redford for work. The 53-year-old man rides the DDOT 38 Plymouth route in the wrong direction on his way to work, Duggan said, just to ensure he has a seat on the bus. That’s what it’s like here.

Riding along a Woodward bus last month, a male rider shared his recent woes with nearby passengers: He was standing on Eight Mile Road in sub-zero temperatures when he flagged down a DDOT bus passing by. To his amazement, the driver simply said, “I’m not working right now.” And she drove off. The next bus didn’t come for some time.

Another rider quickly chimed in with gripes: “I had to wait an hour for one yesterday!”

The mayor, who announced his administration would bring new security cameras for DDOT buses this year and have 50 new vehicles in service this fall, then became a scapegoat for one female rider, who said: “Duggan says the buses gettin’ better, but they’re not; they’re gettin’ worse!”

10 MINUTE WAITS AN ‘INJUSTICE’

That’s not to say metro Detroit’s transit systems used to be in worse shape than the infrastructure of today. Craig, the DetroitTransitHistory.info proprietor, has fond memories of the early 1960s, the time when he discovered his love for buses. The various private operators had problems, Craig says, but the one- to two-hour waits some Detroiters face today were unimaginable. Quotes scattered throughout newspaper clippings from the 1960s he’s collected over the years show riders blubbering about 10- or 15-minute waits.

“Back then, if you waited 10 minutes for a Woodward bus — back 30, 40, 50 years ago — that would be an injustice,” Craig says. “We’ve come a long way, unfortunately, in a downward spiral getting there.” But as ridership levels wavered, the worsening financial conditions of numerous bus operators eventually led to fractured service. So officials and planners set about crafting a solution.

At the time, major metropolitan areas were moving toward regional transit operations, and some local officials were feverishly working to hatch such a plan for metro Detroit on the heels of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Urban Mass Transportation Act. But the initial show of support for a regionalized operation was minimal. Mergers were previously considered, but the 1960s served as a landmark in metro Detroit’s storied history of failed regional cooperation (See sidebar). From this point forward, Detroit’s status in the region as the central core of activity slowly disintegrated, as the lack of cooperation slowly dispersed capital and fractured transit operations outward to the suburbs.

By 1967, state legislators would offer a breath of fresh air with the passage of the Metropolitan Transportation Authorities Act, which formed the Southeast Michigan Transportation Authority (SEMTA). The authority was tasked with merging the operations of the numerous transit systems across metro Detroit.

The problem? State lawmakers failed to grant SEMTA the ability to levy taxes for a dedicated revenue stream. This forced the authority to rely on private sources and state grants to get an efficient regional transit system off the ground.

Not far away in the Rust Belt, when the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority was formed a decade later, voters approved a 1 percent countywide sales tax to fund the authority, paying for nearly 70 percent of the operating budget.

The merger became the difficult part. The 1967 riots in Detroit cut loose tensions between an institutionally racist police department and residents, leaving wounds that still linger today. When Coleman Young, the city’s first black mayor, took office in 1974, those tensions heated up again. But Young was seeking to make decisions that benefited Detroiters, in much the same way suburban leaders have worked for their residents ever since.

To say it was simply Young’s rhetoric that widened the city and suburban racial divide and halted regional transit discussions would be wrong. There were legitimate concerns from Detroit surrounding the governance of a regional authority, something neither side appears to have budged an inch on. In a 2012 Urban Affairs Review article by Jan Nelles, she summed up the simmering issues surrounding SEMTA, which represented a seven-county region (Livingston, Macomb, Monroe, Oakland, St. Clair, Washtenaw and Wayne).

“Detroit was reluctant to give up control to a regional body dominated by suburban interests, and disputed the distribution of representation from each jurisdiction on the governing board,” Nelles writes. “For its part, SEMTA was wary of taking over the DSR’s liabilities, which included a significantly underfunded [pension liability].”

In the early 1970s, then-Gov. William Milliken was at work to merge the two operations because President Gerald Ford had promised $600 million in federal funds (about $2 billion in today’s dollars) for public transit during his presidential campaign, Nelles writes. The Urban Mass Transit Administration (UMTA) would administer the grant, but the agency required some form of a regional authority that included a true merger of the systems as a stipulation for releasing the funds. Things were looking bright as officials reached a compromise in 1976, culminating in the passage of revamped SEMTA legislation.

FORD TO DETROIT: WE’RE SORRY

Johnny Cash once mused to an interviewer that failure should not be dwelled on. Failure, he supposedly said, should be analyzed, so as to not make the same mistake twice.

It’s an adage worth mentioning, as the transit plan being pursued in the 1970s could’ve been a game-changer. And yet metro Detroit continued to fall into the same trap.

Scott Wagner, then an assistant manager for rail technology with SEMTA, recalls the plans with fervor. The main piece of the project, a Woodward Avenue subway line, would’ve run from the Renaissance Center to McNichols Road, where it would surface and follow the corridor’s median. Then, Wagner says, the service would continue northbound into Royal Oak, where it would shift toward Main Street or Washington Avenue (“We were still negotiating with Royal Oak”), and eventually link up with an existing commuter rail service between Pontiac and Detroit.

It didn’t end there. Rail lines were intended to run along Gratiot Avenue as far northeast as the I-94 freeway, according to a story from the Ann Arbor Sun. An additional commuter line between Port Huron and Detroit would’ve been constructed. A flush light rail system would’ve extended into the suburbs. And, yes, downtown’s People Mover was in the pipeline as a way to link these systems up where they converged.

It’s an important point to remember, because bitter locals, out-of-towners, writers parachuting into Detroit and others easily forget that the People Mover, which exists as a lonely and generally useless 2.9-mile fixed-route light rail system above downtown’s business district, was intended to be more.

Carmine Palombo, director of transportation planning at the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG), recalls the plans, as he started work at the planning agency around the same time. He echoes points about the issues that strained relationships between the suburbs and the city over public transit.

“A lot of that is tied to revenue, a lot of that is tied to having two separate and distinct systems that serve different populations,” Palombo says.

The reason there’s no subway running under Woodward Avenue today linking Oakland County and Detroit is a “difference of perceived needs between elected officials,” he says.

Merger discussions continued as late as 1979, culminating in the passage of a half-cent gas tax in the tri-country region for the new transit system, the University of Detroit Mercy report says.

Again, like clockwork, the plan would fall apart due to disagreements between the city and the suburbs. Mayor Young was opposed to SEMTA’s plan for a light-rail system along Woodward. He wanted the high-capacity heavy rail system as a condition of the merger, according to the UDM report. Young and county leaders began a public back-and-forth over the Woodward proposal.

The price tag for Young’s heavy rail technology brought the regional transit project to nearly $1.5 billion, Nelles writes, diminishing lawmakers’ interest.

Wagner says the price shouldn’t have been an issue, pointing to the significance of the $600 million federal commitment. “We could’ve gotten the [Woodward] subway for that kind of money,” he says. “That would’ve been one hell of a start.”

With a successful subway, Wagner says, momentum would’ve likely shifted in favor of mass transit.

What’s readily evident, he says, is metro Detroit had the bones to make mass transit work as late as the 1980s: Between the existing commuter rail and bus services, the $600 million regional proposal floated three decades before would’ve laid the groundwork for modern public transit in Detroit. A 1-percent sales tax to support the project was on the table, he says, potentially generating hundreds of millions of dollars to support capital costs. It never went anywhere.

By the mid-1980s, the lack of a shared vision made the regional transit plan near impossible to complete. SEMTA dissolved a 45-minute commuter train route it had been operating between Detroit and Pontiac for nearly a decade; a year later an Ann Arbor route was cut.

Wagner lived in Ann Arbor during this period and remembers taking the commuter rail line at $15 per month for a train pass, “which was a lot cheaper than driving downtown,” he says.

Amtrak offered to restart service with funds to support a commuter rail line between Joe Louis Arena and Ann Arbor, but local funds were never identified and the project was axed. Although officials ensured that construction of the People Mover would move forward, it would come without the much-needed feeder lines to make it viable, Wagner says.

“The People Mover was never supposed to be standalone project,” he says. “That was supposed to be the downtown distributor for three lines that never got built.”

The People Mover’s bay area at the Joe Louis parking garage was initially thought to be an ideal station for the commuter rail service. When the feeder lines never commenced, the People Mover was eventually extended into Joe Louis Arena, Wagner says.

“We were going to run 11 trains [daily] between Joe Louis and Ann Arbor.”

Then, the $600 million federal commitment, which had survived three presidencies, was revoked. Stifled by personal comments made by Young and a lack of any concrete regional authority in place, President Ronald Reagan yanked the pledge off the table.

The inability to capitalize on the $600 million federal pledge is “arguably the most damaging decision to the Detroit region in the last 50 years,” says Keith Schneider, former director of the Michigan Land Use Institute.

By the end of the decade, SEMTA was dissolved by the state legislature, citing the inability to merge operations in the region. Under the newly minted Regional Transit Coordinating Council, which would operate under SEMCOG as the pass-through agency for grants, the SMART bus system was created. The bus system’s footprint covered Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties.

“The thing just fell apart,” says Craig. “It got so bad that by the time you got to the late ’80s, the sentiment was that we need to scrap the whole thing.”

Nelles writes in Urban Affairs the reason that public transit has gone nowhere in Detroit falls to the relationship between the city and its suburbs.

“Almost all of the challenges to the creation of a single regional transit system in metropolitan Detroit can be traced to power asymmetries that manifested in disagreements between the city and its suburbs over money, power and routes,” she writes.

MAKING THE CITY ‘ACCESSIBLE’

Elisabeth Gerber, professor at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor’s Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, says metro Detroit’s problem is that leaders have never “gone to the whole region and made the case for expanded regional transit.”

In other metropolitan areas with successful developments of mass transit, “you can find a prominent leader who kind of stepped up and made this their issue,” says Gerber, a Washtenaw County representative on the Southeast Michigan Regional Transit Authority (RTA). “For whatever reason, you don’t see that in metro Detroit.”

Bill Bradley, columnist at Next City, an online magazine that covers urban issues, says a lot of people don’t realize how improved transit infrastructure can affect the economy and workforce.

“Economists and lawmakers like to talk about transit-oriented development,” Bradley says. “But I’m far more interested in making jobs more accessible to the people who need them most.”

Bradley, 28, has lived in New York City since 2007. A daily rider of the city’s robust public transit system, Bradley says it’s “undeniably the best, most reliable public transportation system in the country, even for low-income residents [in] the outer boroughs.”

And while he says improved public transit infrastructure in Detroit would likely benefit those who already rely on it the most, a vast operation with increased efficiencies would “make jobs in the suburbs or far-flung parts of the city that were previously out-of-reach more plausible.”

“Detroit is a car city, no doubt,” he adds. “But there are more low-income people in the city sans cars than [most] might think.”

But public transit comes at a cost. Whether it was taxpayers not willing to pump the necessary resources into such initiatives, or leaders failing to hash out a compromise, the fact is, the money to make it work has never materialized.

The capital for transit projects in metro Detroit continues to come from the state gas tax, Palombo points out, and that hasn’t increased since 1987.

“How can you build a transit system when you don’t fund it?” he says.

James Bruckbauer, policy specialist at the Michigan Land Use Institute, says it’d likely take time to win over lawmakers and residents wary of public transit. And even if the money was there, constructing an effective transit system takes time.

Officials need to construct “a plan for transit that the public can get its arms around and understand and see the benefits of, before we start asking people to pay for it,” Bruckbauer says. “Look at Cleveland; they’ve had an established transit system since the 1970s; they’ve been able to show results to their transportation, but it still took them [several] years just to build seven miles of [bus rapid transit].”

FAILED MERGERS AND THE FUTURE

In the 1990s, DDOT and SMART managed to reach one agreement that remains relevant: a regional bus pass. Besides that, the region continued its tradition of failed mergers — lots of talk and studies and promises that fizzle before dying on the planning table.

Discussions were moving forward to consolidate DDOT with SMART as recently as 1994.

Then, according to Crain’s Detroit Business, the two main issues that derailed discussions during the Young administration reappeared: funding and control. The proposal gave Detroit the upper hand in governance of a regional system.

Then-Mayor Dennis Archer stuck to the same argument Young touted, Crain’s reports. Archer felt the proposal “makes sense because the Detroit Department of Transportation’s system has many more buses and riders than SMART.”

Archer told Crain’s at the time: “It would not be unreasonable for the city of Detroit to want to protect its interests.” Archer, Oakland County Executive L. Brooks Patterson, and other leaders never reached a compromise.

By most accounts, the most recent — and relevant — blunder came from former Gov. John Engler’s veto of the proposed Detroit Area Regional Transportation Authority legislation in 2002. Engler axed the bill on his way out the door in 2002 to spite those holding up an eleventh-hour bill that would authorize the construction of 15 charter schools in Detroit.

According to The Michigan Daily, Engler said of his veto: “… if the region couldn’t get its act together on education, it didn’t make sense to help transit.”

So after nearly four decades — four decades of lagging behind other metropolitan areas — metro Detroit was nowhere closer to crafting a regional solution to transit.

That is, until 2012. After 23 previously failed attempts, an effort by the state legislature to establish an effective regional transit authority got the governor’s signature.

Signed into law by Gov. Snyder, the Southeast Michigan Regional Transit Authority (RTA) was created to represent Wayne, Oakland, Macomb and Washtenaw counties. Under the legislation, the 10-member board representing the RTA would be tasked to oversee current transit operators across the four counties and develop a proposed 110-mile bus rapid transit (BRT) system.

The legislation didn’t come without controversy. The RTA’s bylaws show a clear distinction, and, some say, preference to bus options over rail (see sidebar). The authority’s board would need a supermajority to ask voters to approve a tax that would fund future operations and capital costs for the BRT system. To construct or operate a rail line, the board requires a unanimous vote.

And in the face of high expectations, the RTA underperformed in its first year. Its first pick as chief executive officer, John Hertel, stepped down from the job after just four months. When the RTA legislation was approved in 2012, it earmarked $500,000 for startup costs. That wasn’t enough. Hertel cited the lack of funds as a chief reason for quitting. Without additional support, he was unable to hire an administrative staff needed to prepare for a ballot campaign.

And when funding isn’t in place, the temptation to economize hurts more than bureaucracies. There are growing concerns that transit planners working without necessary resources might cut corners while designing a Bus Rapid Transit system, resulting in a phenomenon known as “BRT creep.”

The seminal piece on BRT creep comes from transit planner Dan Malouff. Writing for BeyondDC in 2011, Malouff says the ability to cut back on true BRT elements are endless: Buses running in shared expressway lanes, rather than true dedicated lanes; dedicated stations become “stops;” prepay fare and no priority is given to the buses at stop lights.

“There are a thousand corners like that you can cut that individually may or may not hurt too much, but collectively add up to the difference between BRT and a regular bus,” he writes.

Significantly, the RTA also recently voted to hold off on pursuing a ballot campaign until the 2016 general election. State law says the authority can only go to voters during general elections.

Bruckbauer, of the Michigan Land Use Institute, says patience is key. But as the recent RTA board meeting showed, transit advocates are fed up with waiting. Before the RTA voted to delay the ballot campaign, numerous members of the public urged the board to move forward with a proposal this fall, during Michigan’s gubernatorial election.

The concern was if the 2016 proposal failed, as numerous first-tries have, the RTA could continue operating as an organization essentially living hand-to-mouth, while sending hopes and prayers that the state legislature will chip in some additional help. It might be four years before the authority even receives a dime from a steady revenue source.

Lawmakers recently stripped $2 million for the RTA from a supplemental spending bill already approved by the Senate. Officials say it would support the next CEO hire, but at this point the money hangs in limbo. (A conference committee was scheduled Monday between the House and Senate to reach a compromise on the spending bill and possibly re-insert the RTA earmark. No decision had been made before Metro Times went to print.)

That decision, in particular, comes with a hint of irony: SEMTA, the 1970s regional authority, had troubles because lawmakers didn’t enable it to levy taxes. The current RTA can levy taxes, but it lacks the funding to get its feet off the ground.

Nevertheless, the Snyder administration says it fully supports the $2 million appropriation officials still hope to pass. Exactly why the need for more than $500,000 wasn’t recognized in the first place, though, isn’t clear.

Megan Owens, executive director of the Detroit-based nonprofit Transportation Riders United, tells Metro Times she doesn’t “think anyone realized just how much it was going to take to get this agency up and running.”

After the millions of dollars spent on transit studies over the last four decades, how officials and lawmakers showcased a lack of understanding of what’s required to get the agency off the ground is unfathomable.

It also remains to be seen if the RTA might meet the same fate as SMART. Over the last decade, numerous communities have chosen to opt out of the suburban bus system.

State Rep. Kurt Heise, a Republican from Plymouth, turned heads last year when he introduced a bill that would allow communities to opt-out of the RTA, a stipulation specifically left out of the original legislation.

Heise says the communities he represents all opted out of SMART years ago: “I did not feel it was appropriate for me to bind my communities to a new regional transit authority when they have already affirmatively withdrawn from the existing [service].”

Although Heise concedes Gov. Snyder would likely veto his RTA opt-out bill, the representative says “it’s a potential bargaining chip in any potential Detroit bailout or financial assistance the state might provide.” Heise was referencing the $350 million pledge by Snyder to shore up Detroit’s pensions in its ongoing Chapter 9 bankruptcy petition.

“I do believe that the bill is a bargaining chip,” he says, “if the region is going to put money on the table to help Detroit.”

FOREVER LAGGING BEHIND

Back outside the DIA, Storm prepares to head to the museum to start work for the day. Even he runs into the unpleasant side of metro Detroit transit with his golden egg Woodward route. A couple of years back, SMART cut service into Detroit to only run during peak hours. If Storm misses the bus during those times, he has to transfer to the Detroit Department of Transportation’s (DDOT) Woodward route at the State Fairgrounds.

With DDOT, that usually means waiting. “Sometimes that can take a half hour or more,” he says. But the straight shot SMART route “works out well … it’s fantastic.”

He references the M-1 Rail streetcar, a project Nelles describes in Urban Affairs as something that’s “beginning to look like a People Mover II.” Initially, project backers wanted a light-rail line that cut northbound beyond city limits. That was scaled back to end at Eight Mile Road in 2010.

“For the second time, an ambitious regional transit plan was reduced to a single keystone project located exclusively within Detroit city limits,” Nells writes.

Two years later, M-1 Rail was scaled back even further to its current mode, length and form. Transit advocates still have optimistically praised the streetcar line as an anchor project for a long-term initiative. Plans call for the $140 million, 3.2-mile streetcar to run through downtown Detroit with 11 stops before arriving at Grand Boulevard. Officials recently announced a groundbreaking ceremony set to take place this spring, with the projected first streetcar operating by fall 2016. The hope is, if M-1 Rail is successfully operating before the RTA asks voters to approve a tax to fund operations, metro Detroit residents may grow keen to a regional transit plan.

But if the project’s private backers choose to limit the transit line to its current form, forgoing the possibility of future expansion, the streetcar’s function will be limited. It would increase connectivity between residents and employees of a flourishing area in Detroit. But, in a limited state, it’s hard to imagine residents in Northville or Chesterfield Township seeing the benefits of such a line.

Storm says the issues that plague metro Detroit transit operations cross his mind often. Residents like him who have a straight shot, zero-transfer bus ride could probably get by fine without an automobile. But, for the majority of riders, the operation is a sad state of affairs.

He says he’s supportive of the plan to implement the supposedly more efficient bus rapid transit system. But Storm points to the lack of resources in the current systems and offers a question about the BRT proposal that’s sure to cross the minds of many in the coming years.

“If you can’t manage a bus system [now],” he asks, “How are you going to manage that?”