Sitting in the bright and airy living room of their Detroit home, Frank and Karen Hammer recount the battles involving the Michigan State Fairgrounds they’ve engaged in over the years.

Both are retired now. He worked for General Motors; she held a number of jobs including teaching school and working for a nonprofit social service agency.

Their home is located in the Greenacres neighborhood. Just west of the fairgrounds, the area, like the rest of the city, has been belted by the foreclosure crisis. But the quality of these homes, many of them stately brick Tudors built during the affluent days of the roaring ’20s, has held up over the decades. And a strong neighborhood association, which Frank heads, has helped keep pervasive blight at bay.

The Hammers have lived here for 25 years, and for much of that time events at the nearby fairgrounds, located on the south side of Eight Mile Road just east of Woodward Avenue, have demanded their attention.

Back in the 1990s, after then-Gov. John Engler insisted that the annual state fair be self-supporting, there was a proposal to put a horse racetrack at the site that department store magnate Joseph L. Hudson donated to the people of Michigan in 1904.

A group using the name I.C.A.R.E. (for Inter-county Citizens Achieving Regional Excellence) sprang up in 1996 to fight that plan, which was developed without input from those who would be most affected by it — residents in the surrounding neighborhoods, who were concerned about the noise and traffic the project would bring. Because of their opposition, the proposal was withdrawn.

Four years later, in April 2000, a new idea for developing the fairgrounds was offered. This time the plan was to build hotels, an outdoor concert amphitheater and a racetrack for cars.

I.C.A.R.E. ended up going to court to stop that project, with people from Detroit, Ferndale, Hazel Park and other communities joining together in an effort to fight what they considered to be an inappropriate project.

Again, they emerged victorious.

The string of these and other triumphs ended in 2009, when then-Gov. Jennifer Granholm announced that Michigan could no longer afford to support a tradition that had begun 160 years earlier, when the first state fair was held.

A petition was circulated beseeching Granholm to keep the fair going, and more than 50,000 signatures were collected — but to no avail. There is an epitaph of sorts on the I.C.A.R.E. website:

“The Michigan State Fair was closed by former Governor Jennifer Granholm with the promise that it would cut government costs and be used for something that would produce jobs and tax revenue. Three years later, the fairground is still costing the state money and is another large empty and deteriorated area of Detroit. It’s a sad memorial to venality and incompetence of Michigan’s government.”

Which brings us up to the present, and the reason Frank and Karen Hammer are sitting in their living room, explaining the history of the fairgrounds and the struggles that have surrounded it for nearly two decades.

The fight that is under way now amounts to a winner-take-all match. If current plans to transfer the 157-acre parcel to a private developer are completed, there will be no turning back. There will be a movie theater, and big-box stores and assisted living housing for senior citizens. There will be new housing, and some of the historic structures will be saved. Others will be demolished.

And, according to opponents like the Hammers and others, an incredible opportunity to take advantage of a uniquely situated piece of publicly owned land will be forever lost.

That sentiment was expressed late in 2011, when Karen Hammer and two other I.C.A.R.E. activists, Byna Camden and Bob Lang, sent a letter to Gov. Rick Snyder imploring him to reconsider the decision to sell the fairgrounds.

They want the state fair to return to its longtime home. More than that, though, they would like to see what they consider to be the full potential of the property realized, not by putting it in the hands of commercial interests — although they acknowledge the private sector can play a critical role in all this — but rather by having the fairgrounds used as a tool to help revitalize Detroit and the rest of the region.

“We are missing a rare opportunity to utilize this strategically developed, unique acreage,” they declared in that letter to Snyder.

So far, Gov. Snyder hasn’t listened. Last month, the Michigan Land Bank Fast Track Authority unanimously decided to begin negotiations with Magic Plus LLC, a partnership that includes former Michigan State and NBA basketball star Earvin “Magic” Johnson, Lansing developer Joel Ferguson, and Marvin Beatty, a former deputy commissioner for the Detroit Fire Department and current vice president of the Greektown Casino.

What the Hammers, Bob Lang and others opposed to the current plan want the public to know is that, contrary to the impression generated by coverage in the mainstream media, this isn’t yet a done deal.

The Land Bank, they contend, has the ability to put its foot on the brakes anytime it wants — at least until ownership of the property is turned over to some other entity. Which means that the opportunity remains to go back and open the process back up, allowing for the type of broad input that wasn’t included when the Land Bank issued its original request for proposals, or RFP.

Critics contend that the process has been flawed from the start, with a narrow vision that suffered from a lack of public input and a compressed time frame for potential developers to submit bids.

The end result was a single development proposal that met the state’s requirements.

“They claim that they cast a wide net,” Karen Hammer says. “If that’s true, why did they catch only one fish?”

At the February meeting that featured the announcement that the Magic Plus group had been selected as the designated developer for the fairgrounds property, Land Bank officials described the process that began last year when the Legislature passed two bills “allowing the transfer of the former Michigan State Fairgrounds to the state of Michigan Land Bank Fast Track Authority to return the land to productive use.”

Gov. Snyder signed the bills into law in early April, and the property was quickly turned over to the Land Bank.

Before the plan even got out of the Legislature, there was concern among some that a back-room deal was already in the works.

While transfer of the fairgrounds property was still being debated, Rep. Tom McMillin (R-Rochester Hills) registered his objection to the plan. He didn’t necessarily oppose the idea of the state unloading the property, but he did have a problem with the way the governor wanted to do it.

“Mr. Speaker and members of the House: If the desire is to sell the land, then put it up for sale. I oppose sending the land to the MEDC via Land Bank in order to likely cut deals with select well-connected people. Picking winners and losers is wrong.”

It’s not clear if McMillin had anyone in particular in mind — he didn’t respond to several interview requests made by MT — but Frank Hammer says plans for development of the property were under way well before the legislation McMillin opposed was ever even introduced.

“Joel Ferguson came and met with a group of about 10 of us in the fall of 2011,” Hammer recalls. Hammer was invited because of his position as an officer of the Greenacres Woodward Civic Association.

The developer, Hammer says, sketched out his plans for the fairground project on a napkin.

Community activist Lee Gaddies was at that meeting as well. He confirms what Hammer recalls, and expands upon it.

“This was a done deal before it ever went to Lansing,” Gaddies says.

The meeting, he says, was called by then-state Rep. Jimmy Womack, who represented the area.

“We were told, ‘Here’s the plan, you guys better get on board because the governor’s behind this,” Gaddies says. Like Hammer, Gaddies says that Ferguson “literally drew what he had in mind on a napkin.”

Ferguson, in a phone interview with MT, confirms he attended the meeting Gaddies and Hammer describe, and says he did draw some plans on a napkin, but adds that napkin’s now in the trash because the current plan reflects changes that have been made as result of community input. And more changes are possible.

What he adamantly denies is that somehow he worked behind the scenes to ensure that Magic Plus would be selected as the project’s developer.

He contends the only thing the governor wanted was a first-rate development that put the property back into productive use instead of being mothballed, wasting taxpayer money as it sat idle.

“I’m always eager to meet with those people,” Ferguson says. “I’m not locked into what we’ve proposed. I’m willing to listen to anyone.”

He’s clearly not happy, though, to be listening to a reporter “carry their water” by confronting him with their criticisms.

“They don’t need to come swinging at me though a newspaper,” he says.

The state claims that it wanted vital public input on the project, and the governor appointed five Detroiters — including Frank Hammer — to be on the newly created Fairgrounds Advisory Committee. But the RFP was issued before that committee could even meet, let alone provide any meaningful contributions regarding the type of development the state was seeking. Critics also point out this gave potential developers only 60 days to respond.

Even in an economy struggling to recover from the recession that began when the housing-market bubble burst late in 2007, it would seem that the fairgrounds would be a ripe plum any number of developers would be eager to pluck. It is, after all, the single largest parcel along the Woodward corridor, which stretches from the Detroit River to Pontiac in Oakland County.

As landscape architect Ken Weikal points out, the “footprint” of the fairgrounds is large enough to contain the entire downtown area of either Ferndale or Royal Oak.

The word that keeps coming up again and again when talking with people eager to promote an expansive vision for development of the fairgrounds is “opportunity.” They see the site as having unlimited potential.

But when the Land Bank went looking for developers to buy the land, they found virtually no interest in the property. There were just three responses, only one of which ultimately met the financial criteria required by the state.

“Of the bids submitted in response to the RFP, only the Magic Plus, LLC proposal met the RFP’s minimum financial and design requirements,” the Land Bank announced in a Feb. 8 press release. “All proposals were assessed according to the RFP’s criteria, and with neither the review team nor the MLB [Michigan Land Bank] board knowing the identity of the developers to ensure anonymity of project bidders and process fairness.”

What’s being promised is this, according to the authority: “… an approximately $120 million, 500,000-square-foot mixed-used development that includes retail, residential, green space and entertainment uses. In addition, the plan proposes to renovate and utilize some of the existing buildings.”

There will be a cineplex and restaurants, upscale townhouses, a senior living complex and so-called “big-box” retail such as a Home Depot. Also promised are smaller retail outlets, a small train depot and parking — lots and lots of parking.

What there won’t be, if the developers have their way, is any upfront payment for all this property. In its proposal, the Magic Plus group contends that the “property has little or no value until developed.”

To bolster that point, the group points out that Meijer, which is anchoring a shopping center being built at an adjacent site on the corner of Eight Mile and Woodward on land previously owned by the state, needed to be enticed to locate there with the promise of 20 free acres and other incentives.

Instead of paying for the property and then either building on it or selling off pieces for others to develop, the group is proposing that it pay the state “the amount equal to 1 percent of any of the net lease revenue” the group receives, or 1 percent of the net profit received from any property sales.

As noted by Land Bank officials, it has cost the state about $1 million a year to provide security and maintain the fairgrounds since the last State Fair was last held there in 2009. So there’s good reason, they say, for the governor’s sense of urgency in seeing the property transferred to private ownership.

What’s not just ironic, but downright absurd, is the fact that canceling the fair — which was supposedly done because the state couldn’t afford to keep it going — has actually cost taxpayers much more than it would have if had continued operating.

And it’s not just activists like the Hammers who make that claim.

Steve Jenkins managed the Michigan State Fair during its final two years in Detroit, and was assistant manager before that. In a telephone interview with MT, he points out that, although the state Legislature budgeted $5 million annually for the fair, that money didn’t come out of the state’s coffers but was actually generated by the fair itself. The only time taxpayer money came into play was if revenue didn’t meet the $5 million mark.

That happened in 2009, he says, when the fair fell about $300,000 short of its budget and the state had to make up the difference. The year before that, he says, the fair actually turned a small profit.

“The claim that the fair was a financial burden to the state is grossly unfair,” he says.

Even in years when there was a shortfall, such as 2009, that $300,000 in taxpayer money helped sustain an enterprise that pumped a badly needed $5 million into the local economy.

In terms of economic activity, even in years when there was some subsidy, “you’re still getting great bang for the buck,” he explains. There’s sales taxes generated by the fair, and from sales made at other events held throughout the year. And there’s the income taxes paid to workers. And the money paid to local companies providing services.

“The area has definitely suffered a financial loss by not having the fair held in Detroit,” he says.

What makes that loss even more profound, says Jenkins, is that a strategic plan had finally been put in place that would have enabled the fairground to capitalize on its assets throughout the entire year. By renting out the various buildings and holding a variety of events, the potential was there to turn the fairgrounds into even more of a moneymaker.

“It’s frustrating,” Jenkins says. “We had a plan in place to generate revenue year-round, but we never got the opportunity to fulfill that strategic plan.”

As for the $1 million a year that’s been spent maintaining the fairgrounds in recent years, “that kind of support was never required” when the fair was still being held, says Jenkins.

Looking toward the future, Jenkins suggests that the optimum use for the fairgrounds might be some sort of partnership that incorporates aspects of the development being proposed by Magic Plus with the return of the state fair to its longtime home. He doubts the state would contribute, though, and suggests that the nonprofit sector might be persuaded to step in and cover whatever costs the taxpayers previously picked up.

With big foundations like Kresge spending tens of millions of dollars to help lift up Detroit, having the nonprofit sector kick in $300,000 doesn’t seem out of the question.

Either way, Jenkins says, “The fairground could be a hub of economic activity.”

On that point, it seems, everyone is in agreement. The dispute is over what’s the best way to achieve that.

Landscape architect Ken Weikal has been working with a group calling itself the State Fairgrounds Development Coalition, a loose-knit collection of area residents, business owners and representatives from both nonprofit organizations and local units of government.

Together, they have come up with an alternative vision for the fairgrounds. It’s called META EXPO, with META being an acronym for Michigan Energy Technology Agriculture.

It’s not that they object to components of the Magic Plus proposal — in fact, they say aspects of that plan can be incorporated into what they’d like to see happen at the site.

The difference is a matter of scope and vision.

Rather than putting the whole site into the hands of a private developer, they are proposing a public-private partnership. There would still be a cineplex, for example, and housing.

But instead of a development with a centerpiece they say would look much like other shopping malls already scattered around southeast Michigan — and, in many cases, struggling to retain tenants as the economy sputters along and shopping patterns are changing (think of all the bookstores, for instance, that have gone out of business as a result of losing customers to online sales) — what they envision is a development that focuses on the future instead of the past.

Key to that is public transit. Instead of focusing primarily on the auto — as the Magic Plus proposal does, with its acres and acres of parking lots — the META plan is tied to buses and trains, bicycles and feet.

Helping to ground this vision, making it more than simply some pie-in-the-sky hope, is a development that’s occurred since the Land Bank issued its RFP: The state’s creation in November of the Southeast Michigan Regional Transit Authority.

After 30 years of futility, a governing body that will be able to raise funds for a regional rapid transit system — most likely a rapid bus system to serve the region — and then coordinate other components such as local bus lines and commuter rail — has finally been established.

The significance of that in terms of the fairgrounds can’t be understated.

“It is,” says Karen Hammer, “a complete game-changer.”

And it’s not only people who live around the fairgrounds and are focused primarily on transit who see things that way.

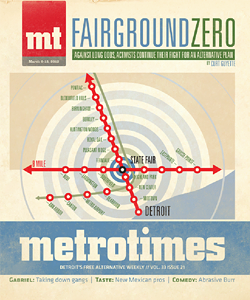

Located on the border of Oakland and Wayne counties, with Macomb nearby, the fairground is ideally located to serve as the transportation hub for the entire region, transit experts say. Along with the Woodward Corridor and Eight Mile, Interstates 75 and 696 are within a few miles, and the Grand Trunk rail line runs along the eastern edge of the fairgrounds property.

Developer Ferguson says he’s all for a strong public transportation component. It only makes sense, he says. For the project to be a success, people need to be able to get there. But where public transit is located, he says, is going to be determined by what the city and state want.

“It’s up to them,” Ferguson says.

Land Bank Executive Director Kim Homan says negotiaions are under way to nail down the details of a development agreement, but the “development team” is fully aware of the RTA and the importance of transit” for the project. But the first meeting of the RTA board is still months away, and with that $1 million a year still being spent to maintain the fairground, it wouldn’t be prudent to “put a hold on the process.”

The way Homan sees it, the fun part hasn’t really begun yet, the part where the “really creative ideas” get tossed into the mix by the public, who will be invited to particpate in a design charette that will be held sometime in the coming months.

The reason for the delay, she says, is that the project’s developers are responding to criticisms that too much of the project is devoted to parking, and are in the process of “tweaking” its plan.

“They know that this isn’t going to survive unless the community supports it,” she says.

On the other hand, Homan says she doesn’t foresee a situation where the whole deal is tossed and everything goes back to square one.

Whatever happens, there appears to be broad recognition that transit has to be a key component of the development.

Megan Owens, director of the Detroit-based nonprofit group Transportation Riders United says that, while the organization hasn’t taken a “formal” position on the fairground issue, the site’s value in terms of transit is obvious.

“It has incredible potential,” she says.

And it’s not just in terms of facilitating the use of public transit, helping people get around without cars, moving seamlessly from Ann Arbor and Metro Airport all along the Woodard Corridor to Pontiac — although that in itself is of tremendous importance to the region’s economic well-being.

Theirs is also the type of development that has sprung up all around the country in areas where mass transit systems have been well established. It is known as “transit-oriented development.”

As the costs of driving continue to climb, it seems that such development — already much in evidence in many other parts of the country — will only continue to grow in importance. Retailers will want to be located where people using pubic transit can easily reach them. Other businesses large and small will want the same thing, because doing so will help attract and keep employees who don’t want to have to rely on a car to get to and from work.

It is that new reality that helped motivate a group of Detroit businesspeople to help fund construction of a light-rail line along Woodward from downtown to midtown in Detroit: because they know it will help to grow their respective businesses in the future.

The potential benefits of having the fairgrounds serve as a hub for intermodal transportation are almost incalculable.

If the target is a transformative development that revitalizes the entire region, the fairgrounds could be the bull’s-eye.

Dan Kinkead, an architect who played a key role in formulating the much-touted Detroit Future City plan that was only recently released, also sees the possibilities inherent in the fairgrounds site.

There is the apparent: “This site can be an important hub for the Regional Transit Authority, a critical intersection where a lot of regional transit lines can come together.”

And then, he says, there is the visionary: “The fairgrounds represent the opportunity to be truly ambitious, and to be a dramatic part of our future … not just for the city of Detroit, but for the entire region.”

It is just that kind of grand-scale thinking that Jim Casha has been stumping for.

Casha, a construction engineer who “builds tunnels” when that kind of work is available, is a native Detroiter who these days divides his time between the city and a farm in Ontario.

The farm explains his business card, which prominently features a rooster, and has the name “Chicken Jim” on it. It’s a little odd, sure, but like he says, it gets the attention of people. Especially in the halls of the state Capitol, where he’s been spending a lot of volunteer time recently, trying to drum up support in the Legislature for the META EXPO plan.

He’s been working with landscape architect Weikal, the Hammers and others to try to get out the word that the Magic Plus plan isn’t a done deal — that there’s still hope a project they think is more beneficial to the overall public interest might have a chance.

His emails about the project tend to end with the line: “Pressing on, with (a lot of) unwavering faith.”

And pushing ahead does take faith, since the META folks say the officials running the Land Bank don’t quite seem to get what he and the others are trying to promote. The criticism of the META plan is that there’s no money behind it.

But that’s looking at development of the fairground through a privatization prism. The META project sees public money as being the catalyst, starting with the federal government doing in Detroit what it has done elsewhere and coming up with funding for the intermodal transportation hub that will help spur private investment.

It is not that the META folks are opposed to everything in the Magic Plus plan. They see aspects of it — the movie theater, say, as well as retail and housing — as being an important piece that the private sector can provide.

The difference is that they would like to see it be at a significantly higher density. Doing so actually produces a much greater economic effect — more than five times as much, they say.

They also see a role for universities as well as private-sector research and development, with a focus on forward-looking technologies: wind and solar energy, advanced auto, and urban agriculture.

Along with those facilities there would also be venues to showcase what is going on, displaying innovations that would draw visitors from around the state, around the country, around the world.

Instead of duplicating the tried — and they would say tired — as the Magic Plus proposal does, they are looking to create something that is innovative.

It is, Weikal says, a matter of good design. Do it right, and the development — and the money — will flow.

The one thing that would be a throwback would be what started it all in the first place: the Michigan State Fair.

They want to see the annual showcase return to the land that was given to the people of Michigan so that the state’s agriculture industry, which remains as vital as ever, and has become a critical part of the revitalization of Detroit, has an urban showcase.

Bob Lang, who is 74 and has lived within shouting distance of the fairgrounds his whole life, remains so passionate about the issue he insisted on following through with a promised interview even though he had to be admitted to the hospital for observation.

He realizes the economic case has to be made if this alternative vision is going to have any chance at all. Especially now, with Magic Plus on the fast track to gaining complete control of the property.

But there’s more than just money involved here, says Lang through coughing fits. There is culture as well. There is the chance for city kids to see calves being born, and there is the opportunity for other kids growing up in rural areas of come and experience life in the big city.

It’s that and everything else a fair that began more than 160 years ago could once again offer Detroit.

And that, in its own way, might be the truly magic idea — the one that seeks to take a leap into the future while continuing to embrace a vital piece of the past.

On the other hand, it might just take a miracle to actually pull off.

Curt Guyette is Metro Times news editor. Contact him at 313-202-8004 or [email protected].

photo credit: Michigan State Fairgrounds photos courtesy Frank Hammer