Late November. Maybe. No, wait. Early December. Hungover. Gray rainy light in the window. The phone rang. It was that voice.

"This is it," he mumbled.

"Huh? Doug?"

"This is it," he repeated. His tone was deep and sour, the usual; but different. Hushed and cryptic this time, burnt as almonds; and it wasn't just the hangover. Shit, we were hungover every day. That was a worry. This time his voice had the absolute absence of God. Any god. Blank. And I could barely hear him; that was the weirdest thing.

"I'm gonna off myself."

"What?"

"I mean it."

"Doug? What the fuck are you talking about?" There was dead silence. That inevitable hush after a person's admission embarrasses the crap out of you, out of both of you. (About Doug: You couldn't say "I love you" to him. But you could slur something like, "I love you, maannn," when you were shitfaced. It'd mean the same, but you'd be relieved of any awkwardness left over from boyhood.) I stayed quiet. Besides, I didn't believe him; I've said similar things. He has too.

But that tone got to me.

"I'm going to off myself."

"What? Are you pissed because I haven't paid you that $300 back yet?"

"No. It's Christmastime. Forget it. Anyway, I won't be needin' it. Shit, it'll fund your Christmas eggnog, you bastard."

"C'mon."

"I'm done."

I thought of his girlfriend, the angel. "What about Sandra?"

"She deserves better," he said.

"Bullshit," I could hear him breathing. I could feel that sadness — the kind that makes it hard to hold a phone to your ear.

"Let's go down to that whorehouse in Nogales," I said. "Remember that time? You just held that girl in your arms, and paid 70 bucks for the privilege? It's that time of year, dude."

"Yeah." Silence.

"You gotta move. And think about it: Kids around the country are singing your songs. You got what you always wanted. You should be celebrating."

After a moment he said something that sounded vaguely apologetic, like, "It was good knowing you," and he hung up.

"He ain't gonna die, if that's what you're thinkin'," I told myself. There was always something so lost about Doug, brittle and fragile as a memory.

When you're a drunk, you have a Superman's tolerance for people doing fucked-up things. But that phone call was really fucked-up. It rattled me. He knew I'd understand. Knew I'd understand whether he went through with it or not. He knew what I knew and more.

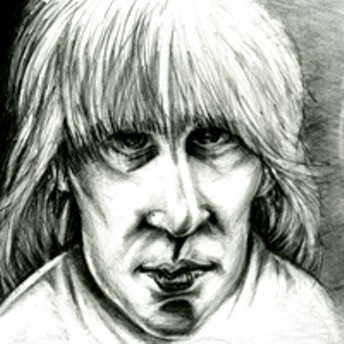

We knew Doug Hopkins. Fuckin' Hopkins. He had these long, flat boat-feet attached to long legs. His arms were long, fingers too, everything long. He was tall in every way. His mind moved faster than his feet could take him. Clumsy as hell: His hasty gait got him tripping, running into things. And the guy couldn't see too well. Had this giant nose like Pete Townshend and a cleft in one eye that split the iris into two parts, sometimes into different colors, depending on the sun, so when you looked into it you immediately wanted to know more about the guy. It was weird like that. He hated it. Girls loved it. He'd keep bangs in his eyes, maybe because of the eye, but mostly because he was shy.

Doug was the funniest man alive, we'd say. And he was. He'd slay anyone in five words, maybe four. His command of the King's English was humbling. His intellect, like his boozing, knew few limits. I figured he had a good mother. He once told me that she gave him Catcher in the Rye when he was a boy — who'd give their pre-teen son Catcher in the Rye? She walked on water.

And bad songs made him livid. He'd bitch a blue streak and point at the radio in his beat-up car, and hurl forth, "You call that a song!" His face would get all pinched up, as if held in place with a vice-grip.

Doug and I shared the same drunken proclivities; the same general feelings of despair, absurdity, pointlessness, and utter loathing for most people around us. The spiritual dimensions of our lives were as tiny as a common fruit fly. Days were riddled with guilt, fear, self-abuse, longing and playing in rock 'n' roll bands at shitty clubs. We were both born in the '60s, but Doug was a little older than me. So he was better at laughing this stuff off; and, because of the Gin Blossoms, he'd seen more success. I mostly wanted to die. But the whole idea of succeeding or failing was a joke ready-made for Doug's cynical jibes. He knew that cynicism was just lazy — dude was a cynical bastard — but his fierce intelligence and sour humor would punch through his seemingly impenetrable bitterness. That's what saved him from coming off like a child.

Sometimes he'd find some grace. Drinking was all about searching out that grace. He discovered it in those fleeting moments of truth in his songs and lyrics, but, in general, he hated himself for not seeing it in the day to day. That level of self-hatred was frustrating — for me, for him and for the many who adored him.

I considered Doug a superstar for scaling the fence out of rehab that time, open-back hospital gown and all. Before that I could see him caught in the surging rush of elation and speed when he drunkenly hopped a southbound freight train from Tempe to downtown Tucson, to the Congress Hotel. He returned with these bizarre tales of trysts in bathrooms and drunks at bus stations.

The guy was a legend in the Phoenix college-town suburb of Tempe, anywhere there was a pool table. One only need listen and look. A debauched Doug episode wouldn't surprise anyone; there wasn't a thing he could confess that'd make anyone love him less. That search was constant and guilt-ridden. His search was almost always drunk.

I remember one phone call. He'd been out of the Gin Blossoms awhile, maybe a year. I said, "Did you see the Blossoms on Letterman the other night?"

"No."

"They played your song."

Not even a pause: "Those bastards are making a killing on my song. Chriiist."

"Well ..."

"How much money will I get for that?"

I guessed at the royalty. "I don't know, probably $1,800 for the first airing."

"That's a good amount."

"Doug, you have no idea what's coming to you."

"I need it."

"Dude, you want the Gin Blossoms album to take off. Look at it like this: Those guys are out working for you. You're gonna be rich. And hate those guys all you want but they're working for you."

"Hmmmmmmmmm."

"What, you want the album to flop?"

"I don't want to see those guys get famous." The line quieted. Then he said, "Those baaaastards."

Doug once told me that he could barely remember writing "Hey Jealousy." He remembered clearly that it was a story about the sister of a singer he'd been in a band with, this beautiful girl that he and everyone else had a crush on but couldn't touch. He had something with her once but he blew it — the drinking. That's all he remembered about writing it. That and he hated the Gin Blossoms singer for changing the word in his lyric; he swapped "drink" with "think." Those lyrics were straight from Doug's daily vocabulary, his usual promise to a new girl. Honest shit.

You can trust me not to drink/And not to sleep around/If you don't expect too much from me/You might not be let down.

Doug was in bad shape when the Blossoms booted him. It was just after the debut album was completed. (New Miserable Experience, how ironic.) The Memphis recording sessions were chaos. He couldn't play guitar sober because his nerves sizzled, and his hands would shake so bad that he couldn't finger chords or strum strings. He'd need the booze to ease the nerves and kill the shakes. But by the time he quelled the tremens he'd be too drunk to play. Oh, the hideous quirks of fate.

The band? I didn't see Doug much when he was in the Gin Blossoms and they ruled Tempe and the SXSW and CMJ conferences. I was back in Los Angeles with my own band. But I was back in Arizona when the Blossoms kicked Doug out. His band mates were, to me, total bastards then — but kids, really; at least emotionally. They were young signees of a major record label — at the mercy of the A&R and lawyerly suits who lived in southern California-cliché homes in the hills above Sherman Oaks. The label mandate was dump Doug — get rid of the guy who built the band and whose songs got the band the record deal — or else. The label had already spent a small fortune recording a first album, which was scrapped. What'd the band know? Even Doug's best friend, with whom he grew up, was a Gin Blossom. The band needed a career and took one. At that point Doug couldn't function as a guitarist or a human being.

The record company weasels abandoned Doug too. There were no phone calls about how he might secure a future as a songwriter. No calls wondering of his well-being. None of it. But one day a label lawyer did call. He ordered Doug to sign over part of his sales share of the New Miserable Experience to his replacement in the band. If he didn't, he wouldn't get a check worth thousands owed him. Ugly shit like that went on. And he hated the way that record turned out. He mostly blamed himself for that.

But you never like it when your friends get famous, especially if it's on your idea and singing your songs.

I enlisted the help of a friend in New York to shop his new and old songs to land a publishing deal. It was looking good because he had two songs that were going to hit it big, kids across America were to about to sing along to Doug's poppy melancholy.

The other thing: Doug had accomplished his life's goal. Jesus.

One time years earlier we were in the home of some B-movie director in the hills above old Hollywood, straight up Ivar Avenue. We'd come to L.A. — drove Doug's beat brown car with all of our shit in it, pissed drunk under desert stars arguing about music and authors the whole way. That rare adrenaline of optimism and beer pumped through the veins. We came to L.A. to get this record deal. But it was all a lie involving this scrawny guy with snow-white skin who sported a lopsided Andy Warhol wig and his "Lady" girlfriend who knew Dylan. ("Lady" because her old man was some kind of English nobleman.) They were, for a moment, our "managers." This couple heard some songs I did, some Doug did, and because my first band had this full-page pimp-out in People magazine — we were picked as stars of the future in an anniversary issue alongside some who actually did become very big stars — some interest floated in from labels and so on. And I felt like a complete has-been at 22. The first marriage was down the shitter; had no money; my band, my life, and whole identity amounted to zippo. Time for Hollywood.

Anyway, the Lady who knew Dylan and Warhol wig "put us up" in the Sunset Palms shithole on Sunset, between La Brea and Highland.

The Lady who knew Dylan also knew this film director. They'd kiss on the cheek when they'd see each other. Pretentious Hollywood shit.

Anyway, this director, this squat guy with a Jewish 'fro and fast sentences, lived in this odd house shaped like a giant golf ball sliced in half. It was raised on stilts off the side of the hill. It stuck out hopelessly just below the Hollywood sign on a foliage-lined street peppered with Spanish Revival houses behind gates, where you could almost hear old-Hollywood ghosts like Ramón Navarro stepping from his swimming pool, breathing in the ivory and cherry blossoms, and heading indoors to mix a highball. The house's interior resembled a kind of opium den, with pillows, incense, tapestries and so on. Only difference was this one had a dizzying, 180-degree view of Hollywood, right at our feet. Stunning stuff.

"Christ," Doug said, "this is Hollywood" He could get used to it. Me too.

So one night we drank this guy's Heinekens and sat on pillows with all of Hollywood below us and watched the original, black-and-white version of Secret Garden on his big-screen. It was comfortable for a change. The film's story, basically about overcoming inner obstacles to discover the beauty around you, all wrapped into this garden metaphor, is beautiful, any way you look at it. Near the end of the movie I looked over at Doug. His face was a mess; scrunched and wet, tears streaming down. He stayed quiet the rest of that night.

The rest of that L.A. trip went like this: We worked on one of Doug's songs on one day, got it sounding pretty good. Worked on one of mine too, which, I'm sure, was awful. We went hungry. Spent what money we had at the bar or liquor store. The rest of the time we bitched, moaned and tossed our personal demons/depressions together into a repulsive little pile like dirty clothes.

Doug developed a mild crush on a friend of an L.A. friend of mine. A "goddess" with a big ass named Mona. He managed a catchy little ditty about her butt, which got us laughing. Days were like that. Somehow we were back in Phoenix; Doug went first. Then he started a new band that sort of became the Gin Blossoms. I forget what I did.

Withdrawls from booze are ugly, an agony you don't want to know. It's like you're in a car accident that freezes for hours and hours in that exact moment of collision and pain. And forget kicking on a cot in an overcrowded state-paid detox ward in the Phoenix projects, surrounded by alcoholic street-urchins shitting their pants and screaming. You'd rather die.

Whenever Doug got sober he'd announce that it was "the bravest thing" he'd ever done. He didn't lie about shit like that. He was a superstar when he'd go through with it. On those rare dry runs Doug could rule the world. He was a force, and he had something to prove to the Gin Blossoms. Some days he'd get up early and begin writing. Sometimes he'd phone up and say, "Man, I got a lot of work done today." He'd follow that with, "A man could work up a mighty thirst doing this." Then he'd say, "Get oiled? I'll bankroll." He knew I didn't have two nickels to rub together. It was his way of saying this: I'm up for drinking if you can come and get me. It was as if a Budweiser was pointing a gun to his head from the inside. He'd reference that Oscar Wilde crusty, and say the only way to get rid of a temptation "is to yield to it."

By then it was drink or live, the doctor said. Drink and I leave, the girlfriend said. He couldn't drink, but he'd sneak out and get oiled anyway. Like George Jones. I hated myself the few times I went over there and collected Doug to go drinking. The look on his girlfriend's face made me want to crawl back inside of my hole. I've been on both sides of that fence, both as an addict with a sober partner and a sober partner to an addict. But I was drunk too. It's that Superman's tolerance for fucked-up things. Doug would drink. Period. And he didn't like going out alone; too many assholes asking too many questions about the Gin Blossoms.

But Doug Hopkins was a songwriter. A bit of guitar hero too, but the songs overshadowed all. He knew it because at that point he called the time he spent writing songs "work." The royalty checks began to arrive, in smallish amounts, which went lengths for personal validation. "Give a man a chance ..." he'd say.

A giant publishing payoff was coming his way, guaranteed. He knew it. He had a song climbing Billboard's Hot 100, it was all over MTV, Top 10 rotation. He had songs on an album that was slowly climbing the Billboard album charts. Who would've guessed that New Miserable Experience would sell more than 2 million copies? That was substantiation, man. I'd often remind him, as if it were my duty, as if by some incredible fluke he'd give in and understand: "Dude, you're in. You did it; you've won. You did what you always wanted to do. Your future's laid out like a string of pearls. You'll write songs for everyone. You're a successful songwriter."

"I'll be a hack," he'd say. "Like Roger in 101 Dalmatians."

His new post-Gin Blossoms songs were evolved — a true embarrassment of riches. They had redemptive qualities, full story-driven narratives and complex truths told simply. All had his signature hooks. I heard a few written from the point of view of a woman. Since he hated his singing voice — he thought its tenor was too deep and low to be of any use — he'd need singers to sing his melodies an octave up. And singers were, he'd always say, "the bane of my existence." See, Doug didn't just mouth melodies and words over chords and call himself a songwriter. Nah. A whole song would come out — the bass lines, tricky harmonies, guitar parts, drum parts, lyrics, even horn parts and a mandolin line once; everything placed perfectly. And his songs felt effortless, their melancholy set in literate and flawlessly metered singsong lines.

It became a challenge among Arizona bands to write a song that could touch any one of Doug's. Nobody could do it.

One newer song was a tearjerker called "My Guardian Angel," the one he wrote about/to Sandra, his girlfriend. He adored her. She endured his bullshit, the suicide attempts and the ugly detoxes — the attendant alcoholic jive. When he was sober they were a couple. She loved the childlike, irrational puppy dog in him; that guy whose incurable introversion became charming and then would wreak complete havoc, but still charm. Doug's pals, one of his post-Gin Blossoms bands, the Pistoleros, had a minor hit with "Guardian Angel" after they got that deal with Hollywood Records. The song received airplay despite having a chorus written and sung in Spanish.

Rarely was there a line of his that I didn't wish I'd written. He was the scholar. He brought everyday sadnesses to life. When I got better at writing in general, I wanted to show him what I did. I never could.

One day I visited him and he'd just finished writing "Found Out About You." The Blossoms were just coming together then.

I arrived at his place — this little brick duplex apartment like countless others near the Arizona State University campus in Tempe. We were going out drinking, I suppose. Was I bankrolling this one? Doug was broke, unemployed and heartbroken.

The room was murky and brown and delicate as a dim rock club on Sunday morning. The desperation was palpable; it had that mammalian odor of male depression, sexual and otherwise. It was as if something was fermenting, not just the tartness of cheap beer in the back of our throats.

The electric company had cut the power. Doug got his through a thick orange extension cord, which slithered through the room's window to the complex's little utility room out back, a good 15 feet away.

A single light from a shadeless lamp shone up the room's edges; a bare, cigarette-marked mattress on the floor with soiled sheets piled in the middle, dirty clothes, empty beer bottles and tipped-over ashtrays. Books everywhere — from Jim Carroll and Camus to stacks of butt glossies (Doug's fondness for the female derriere is famous — that song "Keli Richards" on the first Gin Blossoms A&M EP detailed a tongue-and-cheek longing for the anal porn queen).

He'd been into Badfinger, particularly "Day After Day." That its guitarist-author Pete Ham committed suicide a few years after that song hit wasn't lost on Doug. No, that song had more truth because of it. He wanted a song that profound, a longing that'd last for years.

His then-girlfriend had left him, left him with a black eye. She had cheated on him and suckerpunched his face in the lobby of a downtown venue after an REM show. Those lines I write your name/Drive past your house/Your boyfriend's over/I watch the lights go out ... he lived that. You could read his depression as clearly as his words. He was wrecked by drink and heartbreak. Big dark circles under his eyes. His parents had intervened; got him help. But it didn't help much.

He strummed carefully on a Gibson electric that wasn't plugged in because the pawn shop had his amp. Lyrics were neatly arranged chicken scratches on the back of a crumpled show flier.

He stopped. "This won't make any sense without the bassline." So he plucked out the bass part. "The droning fifth on the pre-chorus will make the singer sound like God," he said. He stopped again because he was so proud of the "AM radio" reference in the lyric. He repeated it.

When he finished I was stunned; jealous enough to want to give up. First thought: How can anyone inject these themes of deception, loneliness and loss into a song that's so fucking power pop?

"That's a hit," I said. I could barely contain the excitement, "That song could rule the world." But we snorted at the very idea of a hit song — that's a foreign idea borne of a foreign language.

That the Blossoms' "Found Out About You" later spent weeks in the Billboard Top 40 was a shocker.

Doug took in beauty everywhere. It'd sometimes freeze him in his tracks. He'd stare over the cinderblock wall in someone's backyard, with beer in hand, at an Arizona sunset that'd descend over acres of suburban rooftops repeating to the horizon, like smears of orange taffy and scorched cotton residue. He'd rave about it. He'd rave about the August monsoons. About Mary and Saint Theresa altars in Latino neighborhoods. He'd buy and love Jesus and Mary of Guadalupe imaged on cheap street-corner souvenirs, on rugs and in frames. He'd be taken by the sadness in those affected hip-swinging shuffles of tender-aged prostitutes along Van Buren; of the innocence lost, unbounded.

A drink was a step toward a shiny new memory; a night made from superhuman cloth — of "let's get lost, boys." A drink colored ennui in brilliant splashes when challenges have all run dry, or when the days are as featureless as a Tempe summer. A drink was a step into light, not out of it. Not out of it; at least not in the beginning. A drink was butterflies and youth and a sky crammed so full of stars that, maybe, life offered a few possibilities that were within reach. A drink was the medicine, man. It became the air, food, chick and water.

Booze made things new again. Doug's was a daily quest for New. Of the countless nights I'd been drunk with Doug, a few ended in ugliness. That's a fine percentage. What we did made sense. You played music, you're unemployable and miserable with zero prospects and the frothy glow duped you into euphoria. My scene was fraught with general apathy and fear; fear of refusal, fear of confident people, fear of faith, heartbreak and rent, everything. Was terrified of my own goddamned shadow; thought of suicide daily. Doug too, as far as I could tell — you could only get so close to the guy, close enough anyway to see a charismatic, gifted and flawed and terrifyingly insecure man.

The misery as it applied then: It was bigger than the argument of rock 'n' roll vs. pumping gas; this was rock 'n' roll vs. there's nothing else in life for you. "What? Are you gonna become an author? That's a laugh. ..."

Doug bought into the promise/myth of Keith Richards, of Van Morrison, of the Jam, of the Replacements, of fucking Hemingway and Rimbaud. No turning back.

My liver never failed like Doug's; the puking and uncontrollable shitting. When his was getting bad his eyes floated in their sockets; lifeless and dead as gravestones. Even when he laughed, his eyes wouldn't. We were scared.

It was a good day if the limbs didn't twitch. Sometimes Doug would lift his arm out ahead of him, outstretch his fingers and marvel at the topside of his hand because it was barely quivering. He'd nod and say, proudly, "Gibraltar." The word became a catchphrase.

"Hey, what's going on today?"

"Gibraltar." It said everything.

One year, in the days leading up to Christmas, we had a series of mean quarters games going. I lived in this cinderblock "band house" in Phoenix. Neighborhood cats routinely snuck in and shat everywhere, including inside of the heater vents so when the heat kicked on the whole house smelled like a litter box. We had a junkie roadie who watched daytime game-shows and black-and-white noir flicks all day, every day. Strippers strode in and out, their heels tapping out savoir rhythms at all hours.

Those games of quarters became famous within a small group of our friends. You have no idea how much beer goes down in the course of a single game — the cases of Old Milwaukee piled up in an instant. You get blind drunk. Blind laughing sloshed. You sit in a circle and attempt to bounce a quarter into a shot glass. Get it in and somebody drinks. If you're good at landing the quarters, you can pick on anybody. The game put a fresh spin on the drinking and the killer insult. You basically played until you puked. Doug would puke in the bathroom trash can, take a breather, and continue to play. He slayed everyone.

One night after a long session of quarters, Doug and I made a pact. We agreed, with eye-contact, that if one of us committed suicide; the other would have to follow. It was a kind of tip-of-the-hat, a leap of faith to each other. We were drunk, but as far as I could tell, serious.

A day or so after that "This Is It" call from Doug, I got another one. It was Sandra's friend, who I barely knew. Sandra couldn't come to the phone. A confusing call from Doug's place wasn't out of the ordinary. The friend's voice sounded weird, like how it does when you have a plugged-up nose, like you've been crying.

"Brian?"

"Yeah."

"Doug's dead."

"What?"

I hung up the phone. The room took a dive.

Doug had stuck a .38 into his mouth and pulled the trigger. He was alone in his Tempe apartment on that December night, discovered the next morning with his legs akimbo, boots on, blood and brains splattered up on the wall and ceiling.

I didn't think he'd actually go through with it. In his mind, of all the things he'd seen in life, little seemed salvageable; there was nothing here for him. When true misery gets you, nothing gets in the way. I understood that. But I thought of Sandra. I thought of his sister, his mom and dad, of the hundreds of friends, ex-bandmates and acquaintances who adored Doug. What about them?

I'll drink of anything to make this world look new again/Drunk, drunk, drunk in the gardens and graves— "Lost Horizons"

A few days ago I was in a party store. A wan cold morning and a holiday feeling in the streets. "Found Out About You" wafted up from the cheap stereo radio sitting behind the bullet-proof glass. I froze. It's nearing Christmas again, it's that time. Every Christmas it's the same. It's been years since Doug died but I can never find any real distance from the guy. I learned volumes from him. For years after his death I was on that same Doug track – I figured I'd drink and do drugs until I expired, basically what Doug did. What the hell, I thought.

But true beauty lives in the grace of the small things — a kiss in the warm weight of spring's first sun, the last days of school, the way Christmas lights summon that weird solitude and childhood memories of days filled of splendor. Such grace isn't easy to find. Once you do, it's still not hard to hit the self-destruct switch. If only he'd hung on. A guy like that — like a few death-skirting addicts I've known — would've emerged on the otherside, after years of battle, some kind of spiritual giant. Besides, the world could've used a lot more songs written by Doug Hopkins. But the man couldn't separate the beauty from the booze. It took me forever to learn how.

I'm in Detroit, of all places. What would Doug say about that? He loved Motown. I can't forget a 22-year-old Doug dancing about a room, all bones and skin and underwear, to the Supremes "Stoned Love." He'd have dug this city; its eerie, ramshackle bars where beer signs hover in shadowy corners like mad gods. Where toasts are raised to the spirit of Holland-Dozier-Holland whenever a jukebox spins another two-and-a-half-minute slab of genius.

How could Doug have known that years later that song he wrote in that horrible little room could still resound, thousands of miles away, drifting out of some radio in some god-forsaken land. That it'd still be on the radio, like the timeless songs he was weaned on — the heartbreaking AM radio melodies he mythologized.

He'd see that light, radiant as a suburban Christmas, shooting in all directions.

If you or someone you know needs of help, you can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (1-800-273-8255 or text 741-741), which provides free and confidential emotional support 24/7.

"Hey Jealousy"

"Found Out About You"

Brian Smith is Metro Times features editor. Send comments to [email protected]