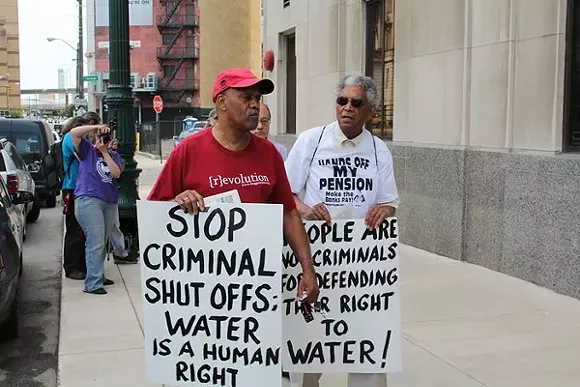

Ryan Felton/Metro Times

A coalition of welfare rights groups rally outside of the Detroit Water & Sewerage Department's main office at 735 W. Randolph in downtown Detroit on Friday, June 6. The groups were protesting efforts by the city to cut water service to residential customers with $150 or more in outstanding fees.

On Tuesday, officials representing the City of Detroit and the Detroit Water & Sewerage Department testified they don't know how many residents in the city are living without access to water in their homes.

But, they said, a temporary moratorium on water shut-offs to assess how many of those residents haven't made arrangements to restore their water service would only be problematic for the utility — and could force additional rate increases on customers.

The testimony came on the second day of a hearing on the city's water shut-off program inside U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Steven Rhodes courtroom in downtown Detroit.

Eric Rothstein, a Chicago-based water consultant who works for the Detroit Water & Sewerage Department (DWSD), testified that a moratorium "conveys to customers who are able to pay their bills" that "they will not face the consequences of a shutoff" for nonpayment.

"I think that the notion of a moratorium — and, in fact, the term of 'moratorium' is problematic," said Rothstein, who was hired to assist the in the formation of a new regional water authority, in a video testimony. On that new authority, Rothstein said the deal would likely "collapse" if financial projections don't materialize, which he says would be impacted by a brief pause of shut-offs.

Rothstein's testimony came as part of an evidentiary hearing called by Rhodes on a request for a temporary restraining order to halt DWSD's aggressive shut-off program, which has drawn international criticism since it began earlier this year.

The department has cut service to roughly 24,000 homes across the city, of which 60 percent have made arrangements to turn their water turned back on, according to DWSD Deputy Director Darryl Latimer. In 2013, DWSD cut service to about 24,000 homes in total.

“Basically, [we've been] breaking records in terms of collections when you compare to previous years," Latimer testified Tuesday.

Asked what caused the year-over-year increase, Latimer said he believes customers have more of an awareness of the shut-off process "and now they're actually coming out."

Of the roughly 40 percent who haven't paid their past-due bills, Latimer attributed that figure to vacant homes, illegal restorations and "some folks that have chosen not to have their service restored." About 30,000 customers are now on payment plans, officials testified today.

The hearing stemmed from a lawsuit filed earlier this year by attorney Alice Jennings on behalf of 10 Detroit residents who have faced water shut-offs. Five of those residents testified Monday to ask U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Steven Rhodes to enact a six-month moratorium on the practice.

Welfare rights advocacy groups and residents opposed to shut-offs have supported the implementation of a water affordability program based on income, rather than the one launched by Mayor Mike Duggan last month. The temporary restraining order asks Rhodes to halt shut-offs for and keep water running until the city puts forth such a plan.

At the center of the hearing was a dispute over whether Rhodes had the authority under bankruptcy statute to decide on the matter. The city argued it was not permitted, while attorneys representing the plaintiffs said otherwise.

A lengthy back-and-forth between the city's attorneys and Rhodes turned on the definition of an "executory contract" in bankruptcy, and if the city has an obligation with its residents to continue providing water service — and, if it didn't, would it be a breach of the contract. It was by far one of the most arcane, yet relevant, discussions in Detroit's bankruptcy, which began July of 2013.

Alexis Wiley, chief of staff for Mayor Duggan, who was given control of DWSD last month, also testified Tuesday.

In response to a question from Jennings, Wiley said Detroiters who don't pay their bills "saddle" other residents with higher costs. The mayor's office wouldn't support a restored moratorium, she said.

“No, we would not support an extension," Wiley said.

During cross-examination with Jennings, Wiley noted she was unsure how many residents in the city are currently living without water.

"I couldn't say exactly," Wiley said.

Jennings said, "You don't know, do you?"

Wiley: "I don't know the number."

"And you don't know how many people are children ... living in homes without water?" Jennings asked

Wiley: "No."

Wiley said there hasn't been an assessment by Duggan's office or DWSD to determine the exact number of residents whose service had been cut, and not yet restored.

One of the issues raised Tuesday by Jennings is that a number of customers have claimed DWSD hasn't followed its own procedures, a point highlighted by the fact outdated shut-off guidelines for employees remain posted on the utility's website. Latimer explained the department has yet to officially approve updated guidelines, so the old rules remain online. He said the rules should be updated by next month.

The ACLU of Michigan and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund also recently unearthed documents which show DWSD tacked on more than $100 million in retroactive sewer fees dating back six years. According to those groups, DWSD attributed the fees to a "systems change."

Nicolete Bateson, chief financial officer for DWSD, testified that the city faced a reduction in cash flow during the month-long moratorium enacted earlier this summer.

Asked if a continued moratorium would create higher costs for DWSD, Bateson said, “There certainly [would be] a reduction in cash flow.”

Besides Wiley and Bateson, Latimer testified for roughly an hour. He focused on the steps DWSD has taken to increase awareness of options for low-income families in need of financial assistance to pay their water bill.

Prior to the moratorium, Latimer said the department was on pace to collect $1.5 million in fees in July; in August, DWSD collected $200,000 in fees. Latimer said the city has been performing 350 to 400 shutoffs per day, down from 700 to 900 prior to Duggan assuming oversight of DWSD.

Rhodes told the courtroom he would take the arguments under advisement and issue a decision on the temporary restraining order, as well as Detroit's motion to dismiss the complaint, at 8:30 a.m. on Monday.